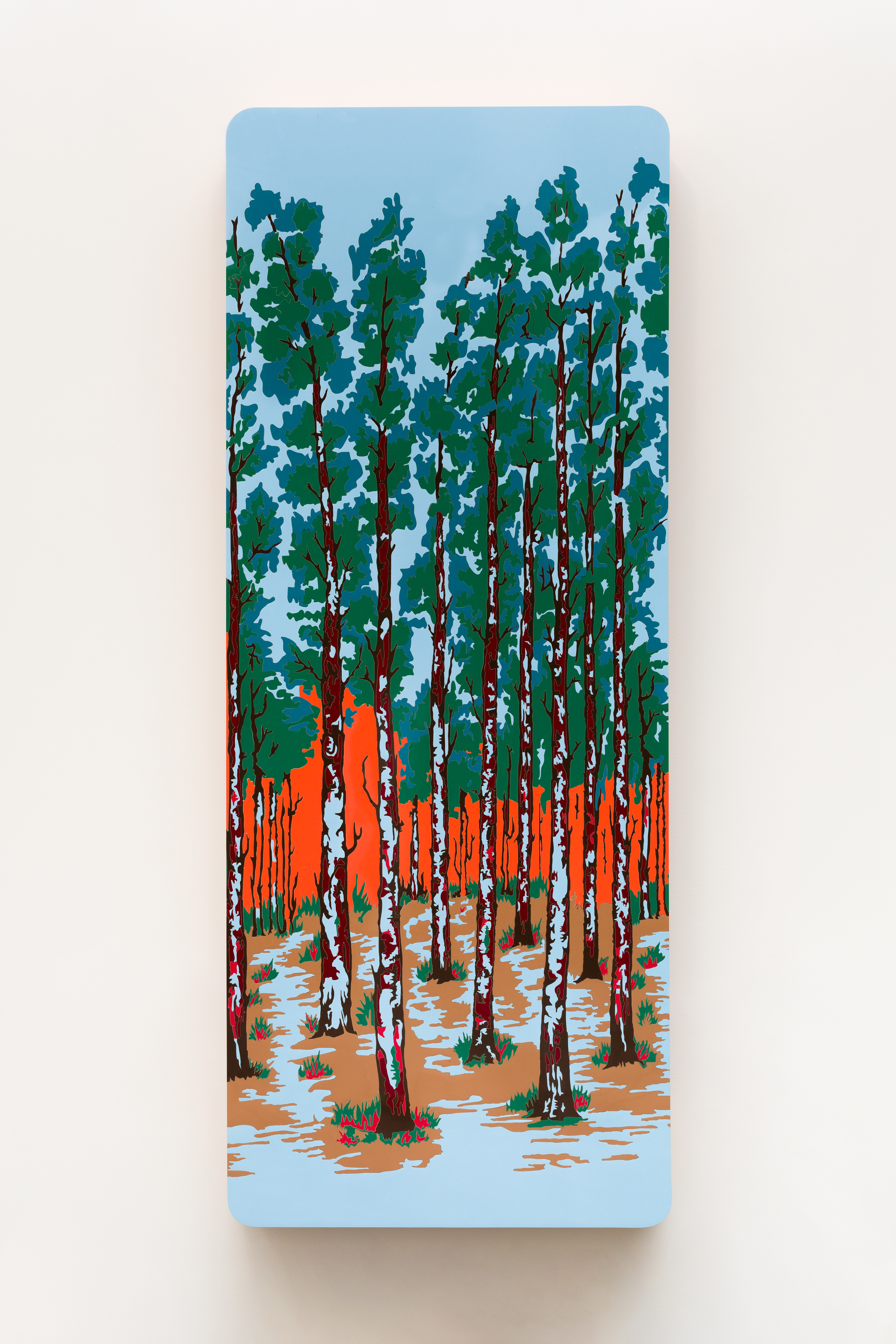

Daniel Acosta, Paisagem Combinatória Vertical G, 2022. Fotos EstudioEmObra.

2022. Daniel Acosta

Exposição “Anti-wide: lembrar a paisagem, esquecer o horizonte”

Texto crítico para a exposição da VERVE, na SP-Arte 2022, em São Paulo

Texto crítico para a exposição da VERVE, na SP-Arte 2022, em São Paulo

Anti-wide: lembrar a paisagem, esquecer o horizonte

As tradições visuais ocidentais de enquadramento e recorte de imagens têm sido alteradas na era digital: andamos à mão com smartphones de telas verticais, que têm nos condicionado não só a visualizar imagens nesse formato, mas também a produzi-las e a entendê-las na verticalidade. Consumimos conteúdos e publicidades realizadas especialmente para esse novo formato portátil; fazemos fotos e vídeos considerando essa verticalidade. Mídias no formato horizontal são consumidas no repouso, em TVs, projetores, monitores de computador ou até mesmo celulares em “posição de descanso”, estabelecendo uma hierarquia de que o que é vertical é transitório e temporário, e o que é horizontal é longevo e mais importante, digno de permacência. Os termos “paisagem” e “retrato” são usualmente utilizados como sinônimos de “horizontal” e “vertical”, respectivamente, reportando a uma generalização desses tipos de pintura de cavalete desde o século XIV, onde a maioria das obras que reproduziam paisagens estabelecia-se na horizontal, e as que representavam retratos, na vertical. É como se a verticalidade, o retrato e o ser humano ocupassem lugares de atividade, enquanto a horizontalidade, a paisagem e a natureza pertencessem ao repouso.

Daniel Acosta (1965 – Rio Grande, RS), assente no princípio da ambiguidade, decide por exibir uma série de objetos escultóricos que apresentam paisagens verticais, investigando possibilidades de trabalhar o tema da paisagem na contemporaneidade sem um magnetismo automático para o formato horizontal. Há, já nessa frase, uma constelação conflituosa de imagens, conceitos e ideias que se chocam e se complementam à primeira vista. Essas obras não atendem totalmente às especificações do que tradicionalmente se espera ao se remeter a um objeto ou a uma escultura, habitando nesse “entre-plataformas” e sendo chamadas de “objetos escultóricos”. Provocativamente, são planos expostos e afixados na parede, próximos à exibição convencional de pinturas – aqui, o acabamento amadeirado no entorno das obras não remete diretamente à tradição da moldura, embora com ela guarde alguma semelhança; mas objetiva conferir uma profundidade mais acentuada a esses planos em que as paisagens portáteis de Acosta residem, ironicamente contornadas por um material artificial que simula madeira. A ironia segue ao objetivar representar paisagens naturais e selvagens em técnicas e materiais altamente tecnológicos e sintéticos, como a fórmica, o MDF e o corte a laser, questionando os campos limítrofes entre as noções de natureza e artificialidade.

Há décadas, Acosta propõe esses recortes naturais que podem ser transportados, assim como nas tradições islâmicas, onde os tapetes funcionavam como jardins portáteis que poderiam ser levados a qualquer lugar, afim de que se mantivesse uma relação de veneração ao cuidado da natureza através da jardinagem. O artista então revisita, na História da arte, a temática da representação de paisagens na pintura, na gravura e na fotografia, usualmente melancólicas e impregnadas de certo bucolismo. Ao olharmos essas paisagens portáteis, ao invés de escaparmos do mundo urbano – no sentido latino de ‘fugere urbem’ –, somos reinseridos na artificialidade impressa pelo ser humano na paisagem.

Ao pensar o espaço e retratar suas florestas e paisagens naturais em materiais sintéticos, Acosta incentiva o questionamento das interferências humanas no ambiente natural, reiterando que a própria noção de naturalidade é artificial. Afinal, as intervenções humanas no ambiente deveriam ser consideradas naturais, na medida em que o ser humano – sendo membro de um ecossistema – molda o espaço às suas necessidades, como propôs Paulo Mendes da Rocha (1928-2021)? A artificialidade seria inerente à produção humana e à sua visão de natureza? Levantando questionamentos e provocando pulverizadas respostas, Acosta nos sugere que a hostilidade não se encontra na selvageria das florestas, mas no pensamento agressivo da sociedade contemporânea e nas suas dinâmicas predatórias de produção e de ocupação do espaço. Nas obras Paisagem de evasão (verde claro) (2021) e Freestandupforest (2010), massas verdes de folhas que coroam copas de árvores se tornam planos vetoriais coloridos, convertidos a uma linguagem tecnológica para que máquinas – porventura – pudessem replicá-los irrestrita e insustentavelmente.

Na série Paisagem Combinatória Vertical, o artista apresenta diversas combinações cromáticas a partir do mesmo desenho – formas compostas por linhas retas e semicírculos, que podem ser lidos como nuvens, fluxos de água ou lava, trechos de solo, campos gramados etc. Elas partem de uma consistente pesquisa que Acosta desenvolve sobre as representações de paisagens nas artes orientais, principalmente pinturas japonesas sobre tecido e papel no período Edo – vale aqui destacar os trabalhos de Itō Jakuchū (1716-1800), Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) e Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858).

Acerca do tema, Acosta ressalta duas importantes características dessas pinturas japonesas incorporadas à sua série: a perspectiva e verticalidade dos planos. A primeira versa sobre a representação oriental do espaço da paisagem, feita a partir de uma verticalidade que prolonga o plano do solo e que não obedece aos mesmos princípios da perspectiva cônica – técnica florentina desenvolvida no século XV e perpetuada aos dias atuais na arte ocidental –, acentuada por Acosta ao fazer as paisagens nesses planos escultóricos milimetricamente chapados. A segunda dá ênfase à preferência por planos verticais ao representar essas paisagens, que, quando necessitavam de maior horizontalidade, eram compostas por vários planos verticais alinhados, como nos biombos dobráveis (byōbu), nas portas de papel translúcido (shoji) e na lógica de aplicação de papeis de parede – elementos verticais que, quando justapostos, resultam em uma composição horizontal.

No panorama da arte brasileira, as obras se conectam com os trabalhos de fórmica de Carlos Fajardo (n. 1941), especialmente com as obras Hora tonal e Hora da chuva, ambas de 1971, em que o artista elabora duas paisagens – horizontais – com a mesma composição de formas, mas com diferenças na escolha das cores das peças marchetadas manualmente.

Uma noção de portabilidade da paisagem na arte contemporânea brasileira análoga à de Acosta pode ser exemplificada através da série de pinturas com tinta acrílica sobre tela chamada Montanhas do Rio, da artista carioca Wanda Pimentel (1943-2019), produzidas na década de 1980. Pimentel representa, a partir de linhas e planos em cores chapadas, em perspectivas com ponto de fuga único, paisagens do Rio de Janeiro enquadradas por caixilhos de janelas, às vezes abertas, às vezes fechadas. São, em seu cerne, paisagens portáteis, mimetizando a abertura de janelas e a apresentação de paisagens quando afixadas na parede. Nessa série, Pimentel propõe que suas paisagens afetivas possam ser presenteadas, transportadas consigo ou exibidas em qualquer lugar que apresente outra – ou nenhuma – paisagem. Além dessa intenção, Acosta (re)apresenta a portabilidade como uma tecnologia humana.

Em Topocampo (vertical) e Topocampo (quadrado), essas paisagens são vistas de cima, como campos topográficos em que não mais a linha, mas o plano do horizonte é apresentado de forma complexa, com sucessivos núcleos de aclives e declives. Acosta propõe a representação do território, da paisagem e da volumetria da terra de forma ambígua: ao mesmo tempo que se configuram como diagramas de território, não são (apenas) representações do espaço, mas objetos espaciais/escultóricos em si mesmo. Temos, então, duas visões confrontantes, mas que se complementam no trabalho do artista: podem ser abordados como representações da natureza, em um aspecto mimético e referencial, mas também podem ser lidos como imanentes, em que o objeto basta em si, não necessitando indispensavelmente de outra coisa a que se refere. Essa discussão híbrida de que trata Acosta, que se refere tanto à dualidade entre referência e imanência, quanto à classificação da obra como “escultura” ou “objeto”, é de natureza semelhante à dos questionamentos levantados por Méret Oppenhein (1913-1985) em Object (Le Déjeuner em fourrure) (1936).

O trabalho de Acosta nos alerta que nos afastamos cada vez mais de perceber que os dispositivos comunicativos, linguísticos e representacionais utilizados pelo ser humano são tecnologias de altíssima sofisticação, além de serem extremamente diversos na pluralidade dos leques culturais – a canônica dualidade antropológica entre natureza e cultura vira uma amálgama híbrida, onde esses dois agentes se confluem. Pensar esses hiperfluxos na arte contemporânea permite a desaceleração de dinâmicas generalizantes e a atenta observação de seus funcionamentos, com pontos críticos que saltam aos olhos e que visam ser debatidos pelo artista. Acosta permite, a partir desse conjunto de trabalhos, repensarmos as noções de natureza e paisagem e escaparmos das amarras representacionais voltadas ao horizonte: lembremos que a representação da natureza pelo ser humano é, portanto, uma meta-ilusão.

/

Anti-wide: remember the landscape, forget the horizon

Western visual traditions of framing and cropping images have been altered in the digital age: we are hand-held with smartphones with vertical screens, which have conditioned us not only to view images in this format, but also to produce and understand them in verticality. We consume content and advertising made especially for this new portable format; we make photos and videos considering this verticality. Media in horizontal format are consumed at rest, on TVs, projectors, computer monitors or even cell phones in the “rest position”, establishing a hierarchy that what is vertical is transitory and temporary, and what is horizontal is lasting and most importantly, worthy of permanence. The terms “landscape” and “portrait” are usually used synonymously with “horizontal” and “vertical”, respectively, referring to a generalization of these types of easel painting since the 14th century, where most works that reproduced landscapes were established horizontally, and those that represented portraits, vertically. It is as if verticality, the portrait and the human being occupy places of activity, while horizontality, the landscape and nature belong to a resting state.

Daniel Acosta (1965 – Rio Grande, RS), based on the principle of ambiguity, exhibits a series of sculptural objects that present vertical landscapes, investigating possibilities of working with the theme of landscape in contemporary times without an automatic magnetism for the horizontal format. There is already, in this sentence, a conflicting constellation of images, concepts and ideas that clash and complement each other at first sight. These works do not fully meet the specifications of what is traditionally expected when referring to an object or a sculpture, inhabiting this “between-platforms” and being called “sculptural objects”. Provocatively, the plans are exposed and affixed to the wall, close to the conventional exhibition of paintings – here, the woody finish around the works does not refer directly to the tradition of the frame, although it bears some resemblance to it; but it aims to give a more accentuated depth to those planes in which Acosta’s portable landscapes reside, ironically contoured by an artificial material that simulates wood. The irony continues by aiming to represent natural and wild landscapes in highly technological and synthetic techniques and materials, such as formica, MDF and laser cutting, questioning the border fields between the notions of nature and artificiality.

For decades, Acosta has proposed these natural cutouts that can be transported, as well as in Islamic traditions, where rugs worked as portable gardens that could be taken anywhere, in order to maintain a relationship of veneration for the care of nature through gardening. The artist then revisits, in the History of Art, the theme of the representation of landscapes in painting, engraving and photography, usually melancholic and impregnated with a certain bucolism. When looking at these portable landscapes, instead of escaping the urban world – in the Latin sense of ‘fugere urbem’ – we are reinserted in the artificiality imprinted by the human being on the landscape.

When thinking about space and portraying forests and natural landscapes in synthetic materials, Acosta encourages the questioning of human interference in the natural environment, reiterating that the very notion of naturalness is artificial. After all, should human interventions in the environment be considered natural, insofar as human beings – being a member of an ecosystem – shape the space to their needs, as proposed by Paulo Mendes da Rocha (1928-2021)? Would artificiality be inherent to human production and its view of nature? Raising questions and provoking pulverized responses, Acosta suggests that hostility is not found in the savagery of forests, but in the aggressive thinking of contemporary society and in its predatory dynamics of production and occupation of space. In the works Paisagem de evação (verde claro) [“Landscape of evasion (light green)] (2021) and Freestandupforest (2010), green masses of leaves that crown treetops become colored vector planes, converted to a technological language so that machines – if it would be the case – could replicate them unrestrictedly and unsustainably.

In the series Paisagem Combinatória Vertical [“Vertical Combinatorial Landscape”], the artist presents several chromatic combinations based on the same design – shapes composed by straight lines and semicircles, which can be read as clouds, water or lava flows, patches of soil, grassy fields, etc. They start from a consistent research that Acosta develops on representations of landscapes in oriental arts, mainly Japanese paintings on fabric and paper in the Edo period – it is worth highlighting the works of Itō Jakuchū (1716-1800), Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) and Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858).

On the subject, Acosta highlights two important characteristics of these Japanese paintings incorporated into his series: the perspective and verticality of the planes. The first deals with the oriental representation of the landscape space, made from a verticality that extends the ground plane and that does not obey the same principles of the conical perspective – a Florentine technique developed in the 15th century and perpetuated to the present day in Western art – , accentuated by Acosta when making the landscapes in these millimetrically flat sculptural planes. The second emphasizes the preference for vertical planes when representing these landscapes, which, when they needed more horizontality, were composed of several aligned vertical planes, as in the folding screens (byōbu), translucent paper doors (shoji) and the logic of applying wallpapers – vertical elements that, when juxtaposed, result in a horizontal composition.

In the Brazilian art panorama, the works connect with the Formica works of Carlos Fajardo (b. 1941), especially with the works Hora tonal and Hora da chuva, both from 1971, in which the artist creates two – horizontal – landscapes with the same composition of shapes, but with differences in the choice of colors of the pieces inlaid manually.

A notion of landscape portability in contemporary Brazilian art similar to that of Acosta can be exemplified through the series of paintings with acrylic paint on canvas called Montanhas do Rio, by the Rio de Janeiro artist Wanda Pimentel (1943-2019), produced in the 1980s. Pimentel represents, from lines and planes in solid colors, in perspectives with a single vanishing point, landscapes of Rio de Janeiro profiled by window frames, sometimes open, sometimes closed. They are, at their core, portable landscapes, mimicking the opening of windows and the presentation of landscapes when affixed to the wall. In this series, Pimentel proposes that his affective landscapes can be presented, transported with them or displayed anywhere that presents another – or no – landscape. In addition to this intention, Acosta (re)presents portability as a human technology.

In Topocampo (vertical) and Topocampo (quadrado) [“Topocampo (square)”], these landscapes are seen from above, as topographic fields in which no longer the line, but the horizon plane is presented in a complex way, with successive nuclei of slopes and topographical curves. Acosta proposes the representation of the territory, the landscape and the volumetry of the land in an ambiguous way: while they are configured as diagrams of territory, they are not (only) representations of space, but spatial/sculptural objects in themselves. We have, then, two confronting visions, but that complement each other in the artist’s work: they can be approached as representations of nature, in a mimetic and referential aspect, but they can also be read as immanent, in which the object is sufficient in itself, not needing indispensably something else to refer to. This hybrid discussion that Acosta deals with, which refers both to the duality between reference and immanence, and to the classification of the work as “sculpture” or “object”, is similar in nature to the questions raised by Méret Oppenhein (1913-1985) in Object (Le Déjeuner in fourrure) (1936).

Acosta’s work warns us that we are increasingly moving away from realizing that the communicative, linguistic and representational devices used by human beings are technologies of very high sophistication, in addition to being extremely diverse in the plurality of cultural matrices - the canonical anthropological duality between nature and culture becomes a hybrid amalgam, where these two agents come together. Thinking about these hyperflows in contemporary art allows the deceleration of generalizing dynamics and the attentive observation of their functioning, with critical points that jump to the eye and that aim to be debated by the artist. Based on this set of works, Acosta allows us to rethink the notions of nature and landscape and escape the representational ties facing the horizon: let us remember that the representation of nature by human beings is, therefore, a meta-illusion.

Texto originalmente publicado na exposição “Anti-wide: lembrar a paisagem, esquecer o horizonte” da VERVE na SP-Arte 2022, de 6 a 10 de abril de 2022

As tradições visuais ocidentais de enquadramento e recorte de imagens têm sido alteradas na era digital: andamos à mão com smartphones de telas verticais, que têm nos condicionado não só a visualizar imagens nesse formato, mas também a produzi-las e a entendê-las na verticalidade. Consumimos conteúdos e publicidades realizadas especialmente para esse novo formato portátil; fazemos fotos e vídeos considerando essa verticalidade. Mídias no formato horizontal são consumidas no repouso, em TVs, projetores, monitores de computador ou até mesmo celulares em “posição de descanso”, estabelecendo uma hierarquia de que o que é vertical é transitório e temporário, e o que é horizontal é longevo e mais importante, digno de permacência. Os termos “paisagem” e “retrato” são usualmente utilizados como sinônimos de “horizontal” e “vertical”, respectivamente, reportando a uma generalização desses tipos de pintura de cavalete desde o século XIV, onde a maioria das obras que reproduziam paisagens estabelecia-se na horizontal, e as que representavam retratos, na vertical. É como se a verticalidade, o retrato e o ser humano ocupassem lugares de atividade, enquanto a horizontalidade, a paisagem e a natureza pertencessem ao repouso.

Daniel Acosta (1965 – Rio Grande, RS), assente no princípio da ambiguidade, decide por exibir uma série de objetos escultóricos que apresentam paisagens verticais, investigando possibilidades de trabalhar o tema da paisagem na contemporaneidade sem um magnetismo automático para o formato horizontal. Há, já nessa frase, uma constelação conflituosa de imagens, conceitos e ideias que se chocam e se complementam à primeira vista. Essas obras não atendem totalmente às especificações do que tradicionalmente se espera ao se remeter a um objeto ou a uma escultura, habitando nesse “entre-plataformas” e sendo chamadas de “objetos escultóricos”. Provocativamente, são planos expostos e afixados na parede, próximos à exibição convencional de pinturas – aqui, o acabamento amadeirado no entorno das obras não remete diretamente à tradição da moldura, embora com ela guarde alguma semelhança; mas objetiva conferir uma profundidade mais acentuada a esses planos em que as paisagens portáteis de Acosta residem, ironicamente contornadas por um material artificial que simula madeira. A ironia segue ao objetivar representar paisagens naturais e selvagens em técnicas e materiais altamente tecnológicos e sintéticos, como a fórmica, o MDF e o corte a laser, questionando os campos limítrofes entre as noções de natureza e artificialidade.

Há décadas, Acosta propõe esses recortes naturais que podem ser transportados, assim como nas tradições islâmicas, onde os tapetes funcionavam como jardins portáteis que poderiam ser levados a qualquer lugar, afim de que se mantivesse uma relação de veneração ao cuidado da natureza através da jardinagem. O artista então revisita, na História da arte, a temática da representação de paisagens na pintura, na gravura e na fotografia, usualmente melancólicas e impregnadas de certo bucolismo. Ao olharmos essas paisagens portáteis, ao invés de escaparmos do mundo urbano – no sentido latino de ‘fugere urbem’ –, somos reinseridos na artificialidade impressa pelo ser humano na paisagem.

Ao pensar o espaço e retratar suas florestas e paisagens naturais em materiais sintéticos, Acosta incentiva o questionamento das interferências humanas no ambiente natural, reiterando que a própria noção de naturalidade é artificial. Afinal, as intervenções humanas no ambiente deveriam ser consideradas naturais, na medida em que o ser humano – sendo membro de um ecossistema – molda o espaço às suas necessidades, como propôs Paulo Mendes da Rocha (1928-2021)? A artificialidade seria inerente à produção humana e à sua visão de natureza? Levantando questionamentos e provocando pulverizadas respostas, Acosta nos sugere que a hostilidade não se encontra na selvageria das florestas, mas no pensamento agressivo da sociedade contemporânea e nas suas dinâmicas predatórias de produção e de ocupação do espaço. Nas obras Paisagem de evasão (verde claro) (2021) e Freestandupforest (2010), massas verdes de folhas que coroam copas de árvores se tornam planos vetoriais coloridos, convertidos a uma linguagem tecnológica para que máquinas – porventura – pudessem replicá-los irrestrita e insustentavelmente.

Na série Paisagem Combinatória Vertical, o artista apresenta diversas combinações cromáticas a partir do mesmo desenho – formas compostas por linhas retas e semicírculos, que podem ser lidos como nuvens, fluxos de água ou lava, trechos de solo, campos gramados etc. Elas partem de uma consistente pesquisa que Acosta desenvolve sobre as representações de paisagens nas artes orientais, principalmente pinturas japonesas sobre tecido e papel no período Edo – vale aqui destacar os trabalhos de Itō Jakuchū (1716-1800), Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) e Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858).

Acerca do tema, Acosta ressalta duas importantes características dessas pinturas japonesas incorporadas à sua série: a perspectiva e verticalidade dos planos. A primeira versa sobre a representação oriental do espaço da paisagem, feita a partir de uma verticalidade que prolonga o plano do solo e que não obedece aos mesmos princípios da perspectiva cônica – técnica florentina desenvolvida no século XV e perpetuada aos dias atuais na arte ocidental –, acentuada por Acosta ao fazer as paisagens nesses planos escultóricos milimetricamente chapados. A segunda dá ênfase à preferência por planos verticais ao representar essas paisagens, que, quando necessitavam de maior horizontalidade, eram compostas por vários planos verticais alinhados, como nos biombos dobráveis (byōbu), nas portas de papel translúcido (shoji) e na lógica de aplicação de papeis de parede – elementos verticais que, quando justapostos, resultam em uma composição horizontal.

No panorama da arte brasileira, as obras se conectam com os trabalhos de fórmica de Carlos Fajardo (n. 1941), especialmente com as obras Hora tonal e Hora da chuva, ambas de 1971, em que o artista elabora duas paisagens – horizontais – com a mesma composição de formas, mas com diferenças na escolha das cores das peças marchetadas manualmente.

Uma noção de portabilidade da paisagem na arte contemporânea brasileira análoga à de Acosta pode ser exemplificada através da série de pinturas com tinta acrílica sobre tela chamada Montanhas do Rio, da artista carioca Wanda Pimentel (1943-2019), produzidas na década de 1980. Pimentel representa, a partir de linhas e planos em cores chapadas, em perspectivas com ponto de fuga único, paisagens do Rio de Janeiro enquadradas por caixilhos de janelas, às vezes abertas, às vezes fechadas. São, em seu cerne, paisagens portáteis, mimetizando a abertura de janelas e a apresentação de paisagens quando afixadas na parede. Nessa série, Pimentel propõe que suas paisagens afetivas possam ser presenteadas, transportadas consigo ou exibidas em qualquer lugar que apresente outra – ou nenhuma – paisagem. Além dessa intenção, Acosta (re)apresenta a portabilidade como uma tecnologia humana.

Em Topocampo (vertical) e Topocampo (quadrado), essas paisagens são vistas de cima, como campos topográficos em que não mais a linha, mas o plano do horizonte é apresentado de forma complexa, com sucessivos núcleos de aclives e declives. Acosta propõe a representação do território, da paisagem e da volumetria da terra de forma ambígua: ao mesmo tempo que se configuram como diagramas de território, não são (apenas) representações do espaço, mas objetos espaciais/escultóricos em si mesmo. Temos, então, duas visões confrontantes, mas que se complementam no trabalho do artista: podem ser abordados como representações da natureza, em um aspecto mimético e referencial, mas também podem ser lidos como imanentes, em que o objeto basta em si, não necessitando indispensavelmente de outra coisa a que se refere. Essa discussão híbrida de que trata Acosta, que se refere tanto à dualidade entre referência e imanência, quanto à classificação da obra como “escultura” ou “objeto”, é de natureza semelhante à dos questionamentos levantados por Méret Oppenhein (1913-1985) em Object (Le Déjeuner em fourrure) (1936).

O trabalho de Acosta nos alerta que nos afastamos cada vez mais de perceber que os dispositivos comunicativos, linguísticos e representacionais utilizados pelo ser humano são tecnologias de altíssima sofisticação, além de serem extremamente diversos na pluralidade dos leques culturais – a canônica dualidade antropológica entre natureza e cultura vira uma amálgama híbrida, onde esses dois agentes se confluem. Pensar esses hiperfluxos na arte contemporânea permite a desaceleração de dinâmicas generalizantes e a atenta observação de seus funcionamentos, com pontos críticos que saltam aos olhos e que visam ser debatidos pelo artista. Acosta permite, a partir desse conjunto de trabalhos, repensarmos as noções de natureza e paisagem e escaparmos das amarras representacionais voltadas ao horizonte: lembremos que a representação da natureza pelo ser humano é, portanto, uma meta-ilusão.

/

Anti-wide: remember the landscape, forget the horizon

Western visual traditions of framing and cropping images have been altered in the digital age: we are hand-held with smartphones with vertical screens, which have conditioned us not only to view images in this format, but also to produce and understand them in verticality. We consume content and advertising made especially for this new portable format; we make photos and videos considering this verticality. Media in horizontal format are consumed at rest, on TVs, projectors, computer monitors or even cell phones in the “rest position”, establishing a hierarchy that what is vertical is transitory and temporary, and what is horizontal is lasting and most importantly, worthy of permanence. The terms “landscape” and “portrait” are usually used synonymously with “horizontal” and “vertical”, respectively, referring to a generalization of these types of easel painting since the 14th century, where most works that reproduced landscapes were established horizontally, and those that represented portraits, vertically. It is as if verticality, the portrait and the human being occupy places of activity, while horizontality, the landscape and nature belong to a resting state.

Daniel Acosta (1965 – Rio Grande, RS), based on the principle of ambiguity, exhibits a series of sculptural objects that present vertical landscapes, investigating possibilities of working with the theme of landscape in contemporary times without an automatic magnetism for the horizontal format. There is already, in this sentence, a conflicting constellation of images, concepts and ideas that clash and complement each other at first sight. These works do not fully meet the specifications of what is traditionally expected when referring to an object or a sculpture, inhabiting this “between-platforms” and being called “sculptural objects”. Provocatively, the plans are exposed and affixed to the wall, close to the conventional exhibition of paintings – here, the woody finish around the works does not refer directly to the tradition of the frame, although it bears some resemblance to it; but it aims to give a more accentuated depth to those planes in which Acosta’s portable landscapes reside, ironically contoured by an artificial material that simulates wood. The irony continues by aiming to represent natural and wild landscapes in highly technological and synthetic techniques and materials, such as formica, MDF and laser cutting, questioning the border fields between the notions of nature and artificiality.

For decades, Acosta has proposed these natural cutouts that can be transported, as well as in Islamic traditions, where rugs worked as portable gardens that could be taken anywhere, in order to maintain a relationship of veneration for the care of nature through gardening. The artist then revisits, in the History of Art, the theme of the representation of landscapes in painting, engraving and photography, usually melancholic and impregnated with a certain bucolism. When looking at these portable landscapes, instead of escaping the urban world – in the Latin sense of ‘fugere urbem’ – we are reinserted in the artificiality imprinted by the human being on the landscape.

When thinking about space and portraying forests and natural landscapes in synthetic materials, Acosta encourages the questioning of human interference in the natural environment, reiterating that the very notion of naturalness is artificial. After all, should human interventions in the environment be considered natural, insofar as human beings – being a member of an ecosystem – shape the space to their needs, as proposed by Paulo Mendes da Rocha (1928-2021)? Would artificiality be inherent to human production and its view of nature? Raising questions and provoking pulverized responses, Acosta suggests that hostility is not found in the savagery of forests, but in the aggressive thinking of contemporary society and in its predatory dynamics of production and occupation of space. In the works Paisagem de evação (verde claro) [“Landscape of evasion (light green)] (2021) and Freestandupforest (2010), green masses of leaves that crown treetops become colored vector planes, converted to a technological language so that machines – if it would be the case – could replicate them unrestrictedly and unsustainably.

In the series Paisagem Combinatória Vertical [“Vertical Combinatorial Landscape”], the artist presents several chromatic combinations based on the same design – shapes composed by straight lines and semicircles, which can be read as clouds, water or lava flows, patches of soil, grassy fields, etc. They start from a consistent research that Acosta develops on representations of landscapes in oriental arts, mainly Japanese paintings on fabric and paper in the Edo period – it is worth highlighting the works of Itō Jakuchū (1716-1800), Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) and Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858).

On the subject, Acosta highlights two important characteristics of these Japanese paintings incorporated into his series: the perspective and verticality of the planes. The first deals with the oriental representation of the landscape space, made from a verticality that extends the ground plane and that does not obey the same principles of the conical perspective – a Florentine technique developed in the 15th century and perpetuated to the present day in Western art – , accentuated by Acosta when making the landscapes in these millimetrically flat sculptural planes. The second emphasizes the preference for vertical planes when representing these landscapes, which, when they needed more horizontality, were composed of several aligned vertical planes, as in the folding screens (byōbu), translucent paper doors (shoji) and the logic of applying wallpapers – vertical elements that, when juxtaposed, result in a horizontal composition.

In the Brazilian art panorama, the works connect with the Formica works of Carlos Fajardo (b. 1941), especially with the works Hora tonal and Hora da chuva, both from 1971, in which the artist creates two – horizontal – landscapes with the same composition of shapes, but with differences in the choice of colors of the pieces inlaid manually.

A notion of landscape portability in contemporary Brazilian art similar to that of Acosta can be exemplified through the series of paintings with acrylic paint on canvas called Montanhas do Rio, by the Rio de Janeiro artist Wanda Pimentel (1943-2019), produced in the 1980s. Pimentel represents, from lines and planes in solid colors, in perspectives with a single vanishing point, landscapes of Rio de Janeiro profiled by window frames, sometimes open, sometimes closed. They are, at their core, portable landscapes, mimicking the opening of windows and the presentation of landscapes when affixed to the wall. In this series, Pimentel proposes that his affective landscapes can be presented, transported with them or displayed anywhere that presents another – or no – landscape. In addition to this intention, Acosta (re)presents portability as a human technology.

In Topocampo (vertical) and Topocampo (quadrado) [“Topocampo (square)”], these landscapes are seen from above, as topographic fields in which no longer the line, but the horizon plane is presented in a complex way, with successive nuclei of slopes and topographical curves. Acosta proposes the representation of the territory, the landscape and the volumetry of the land in an ambiguous way: while they are configured as diagrams of territory, they are not (only) representations of space, but spatial/sculptural objects in themselves. We have, then, two confronting visions, but that complement each other in the artist’s work: they can be approached as representations of nature, in a mimetic and referential aspect, but they can also be read as immanent, in which the object is sufficient in itself, not needing indispensably something else to refer to. This hybrid discussion that Acosta deals with, which refers both to the duality between reference and immanence, and to the classification of the work as “sculpture” or “object”, is similar in nature to the questions raised by Méret Oppenhein (1913-1985) in Object (Le Déjeuner in fourrure) (1936).

Acosta’s work warns us that we are increasingly moving away from realizing that the communicative, linguistic and representational devices used by human beings are technologies of very high sophistication, in addition to being extremely diverse in the plurality of cultural matrices - the canonical anthropological duality between nature and culture becomes a hybrid amalgam, where these two agents come together. Thinking about these hyperflows in contemporary art allows the deceleration of generalizing dynamics and the attentive observation of their functioning, with critical points that jump to the eye and that aim to be debated by the artist. Based on this set of works, Acosta allows us to rethink the notions of nature and landscape and escape the representational ties facing the horizon: let us remember that the representation of nature by human beings is, therefore, a meta-illusion.

Texto originalmente publicado na exposição “Anti-wide: lembrar a paisagem, esquecer o horizonte” da VERVE na SP-Arte 2022, de 6 a 10 de abril de 2022

Daniel Acosta, Paisagem Combinatória Vertical M2, 2022.

Daniel Acosta, Paisagem Combinatória Vertical M1, 2022.

Daniel Acosta, Paisagem Combinatória Vertical P3, 2022.

Daniel Acosta, Paisagem Combinatória Vertical P2, 2022.

Daniel Acosta, Paisagem Combinatória Vertical P1, 2022.

Daniel Acosta, Freestandupforest, 2010.

Daniel Acosta, Topocampo

(quadrado), 2021.

Daniel Acosta, Topocampo

(vertical), 2021.