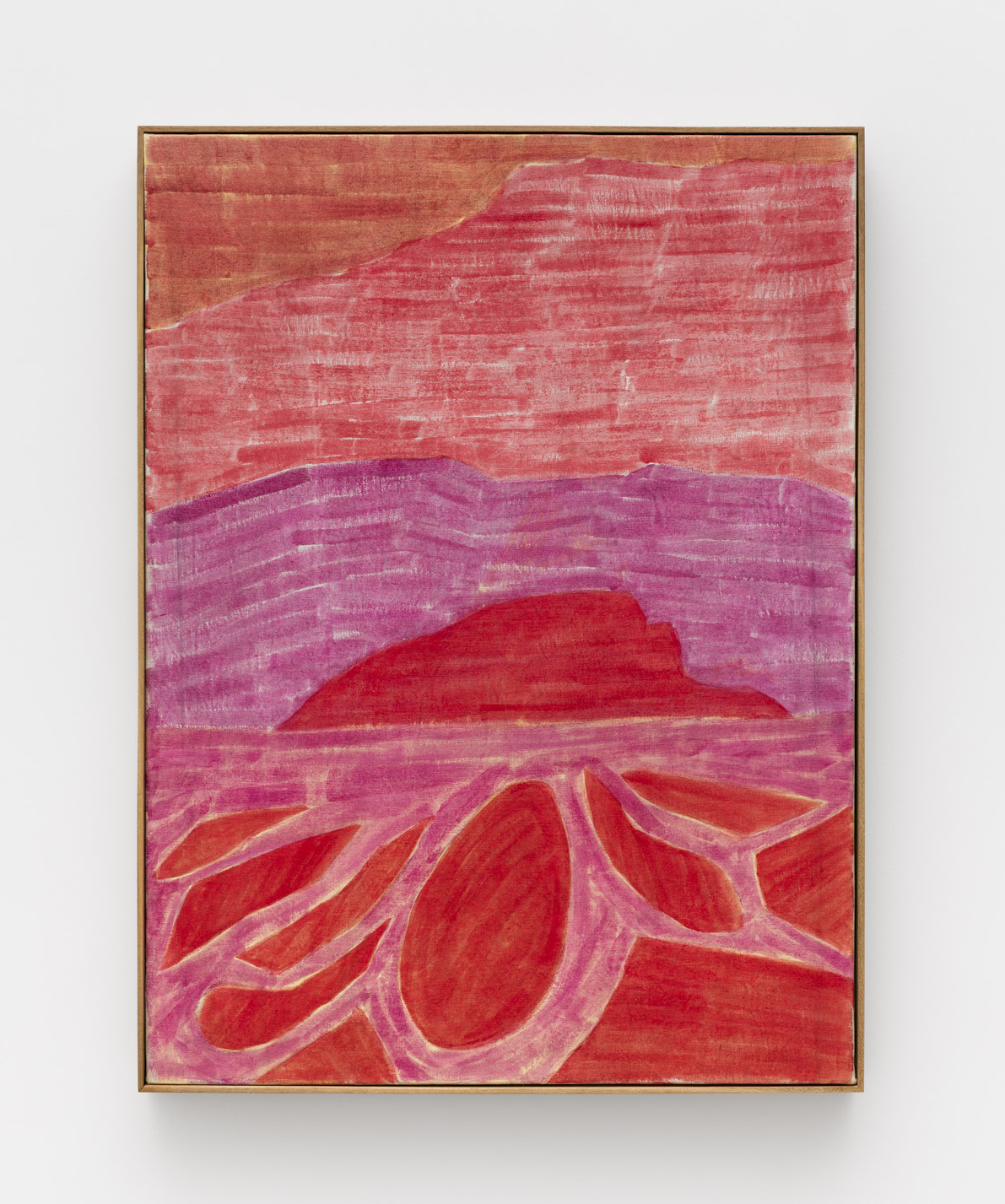

Diambe, Sensação térmica, vistas da exposição, 2024.

2024. Diambe

Sensação térmica

Curadoria da exposição individual da artista na galeria Simões de Assis, em São Paulo

WEB

Curadoria da exposição individual da artista na galeria Simões de Assis, em São Paulo

WEB

25.05-20.07.2024

Galeria Simões de Assis, São Paulo

A expandir sua poética através de fabulações de seres que podem ser assimilados como paisagens, figuras zoomórficas, alimentos, entidades trans-espécies e manifestações de uma memorabilia sonhada, Diambe (Rio de Janeiro, 1993) reverencia a inventividade efervescente que responde a máculas e muralhas impostas a corpos dissidentes na contemporaneidade. Em seu processo criativo, materializa criaturas que habitam uma natureza poderosa e autônoma, cujo poder sobrepuja o do ser humano e proporciona um escape de uma ilusória situação de dominação antropocêntrica. Paralelamente, na presente exposição, Diambe discute como culturas, em diversos contextos geográficos, consideram a temperatura local como fator determinante na escolha dos materiais a comporem seus objetos, endereçando a assimetria na reciprocidade de recepção sociocultural estabelecida pela diáspora africana no Brasil.

Em Sensação térmica, materialização de um sonho perpétuo ignizado por Diambe, apresentam-se pinturas que manifestam escolhas cromáticas calorosas, esculturas gotejadas em bronze com pátinas coloridas e bases de argila crua que racham em resposta ao tempo. As obras expostas nessa ocasião foram produzidas em um momento crítico de temperatura ambiental no início de 2024, com sensação térmica maior que 60 graus Celsius em algumas cidades do sudeste brasileiro. Ar e fogo confundiam-se. O calor alucinante atravessava não somente a matéria, mas a subjetividade posta em fogo no estabelecimento de uma poética do delírio. As gotas de suor que escorrem pelo corpo dançante. A saliva morna que recebe a água fresca. O suco da fruta mordida que colore o queixo e escorre pelo peito aberto.

Nesse contexto de assombroso fervor, o transporte das esculturas em cera do ateliê de Diambe para a fundição em metal tornou-se crítico: os corpos derretiam, desmontavam, metamorfoseavam-se em resposta à fulminante onda de calor. Esse torpor também causa uma zona de descontrole, estabelecendo limites desobedientes sobre a manipulação da cera de abelha que molda as esculturas. Desse modo, Diambe não detém total autoridade plástica sobre a matéria, mas respeita sua própria agência, sua multiplicidade vital e suas delirantes possibilidades de comportamento. A partir de profunda intimidade com os elementos plásticos, congrega em torno do calor uma relação colaborativa com os materiais, sempre em trabalho sinérgico e ação mútua.

Depois de confeccionados os moldes, receptáculos que transfeririam suas formas e entidades ao bronze incandescente, os seres em cera retornavam da oficina de fundição a Diambe em pedaços, logo derretidos novamente para corporificar outras subjetividades e produzir novas esculturas com o mesmo material, já impregnado de tantos ciclos de vida e morte. No décimo primeiro andar de um edifício no centro de São Paulo – repleto de frutos, vegetais e raízes colhidas na Mata Atlântica, na floresta amazônica ou negociadas em mercados no Benin –, o aroma que exalava da cera de abelha reaquecida por Diambe atraía frequentemente um pequeno enxame que retornava, em transe, ciclicamente à matéria que havia criado. A preparação de novos corpos desencadeava um chamado aos seres que produziram aquela massa plástica, em um reencontro no momento da transformação material. Esse ecológico fluxo cíclico sugere, inclusive, uma postura harmônica e sustentável de lidar com a matéria, em constante mutação.

Apesar das potências poéticas do calor, Diambe também alerta para os exílios climáticos e o racismo ambiental, a denunciar que as mudanças causadas pelo aquecimento global afetam de forma mais voraz pessoas com corpos dissidentes e grupos sociais marginalizados. Sua prática artística é perpassada pela temperatura desde quando ateava fogo em monumentos públicos que reverenciam ícones totalitaristas que, mesmo estáticos, continuam a violentar corpos e corroer histórias. O calor, por outro lado, também serve como analogia à entropia social causada pelos sistemas que mantêm predatórias dinâmicas colonialistas e imperialistas.

Ao fundir corpos de diferentes âmbitos biológicos e espirituais, Diambe incorpora entidades híbridas que desafiam categorizações e encorajam relações mais respeitosas em uma natureza que pode ser aplicada às esferas sociais. Sendo pessoa negra, desobediente da binariedade de gênero, Diambe entende o corpo como lugar e o lugar como corpo, em uma espelhada geografia sempre política: “o assentamento (também chamado de ibá) no candomblé é, ao mesmo tempo, a morada do orixá, o próprio orixá materializado e o local onde a relação entre pessoa e orixá se faz” [1]. Suas pinturas em têmpera de ovo retomam a origem da técnica milenar originária do nordeste africano, encontrando-se na indeterminação entre paisagens figurativas, seres surrealistas, abstrações cromáticas e outras miríades de possibilidades de existência. Seus trabalhos acontecem propositalmente em uma zona limiar, inegociavelmente híbrida, a amalgamar reinos naturais e metafísicos.

Em respeito à individualidade dos seres que cria e põe no universo, Diambe escolhe que suas esculturas em bronze fundido sejam únicas, sem outras edições. Dessa forma, obedece a epistemologias ancestrais que entendem a criação – artística, nesse caso, mas também de qualquer outra natureza – como provedora de agência, dotando um ser de corpo e integrando-o em dinâmicas naturais como indivíduos que, embora autônomos, não existem sem comunidades harmônicas de cooperação.

Através de sistemas de saberes da diáspora africana e de tradições amefricanas [2], as criações e corporificações de Diambe se relacionam com a noção de alimento, de oferenda, como combustível do corpo e da alma. Comer é, portanto, exercer a sua própria divindade e a do alimento, irradiando energia, prazer, felicidade e alegria de viver. Oferendar isso ao mundo abarca noções dilatadas de tempo ao criar entidades que, postas nesse banquete-encruzilhada, vão durar muito mais tempo que seu próprio corpo, que os vegetais moldados que constituem partes das esculturas e que o ovo utilizado na conservação da vivacidade dos pigmentos na têmpera. Ao reconhecer a perecibilidade do próprio corpo, Diambe sonha em direção a uma oferenda mais duradoura em temporalidades que extrapolam certas noções de vida.

Notas

[1] MARQUES, Lucas. “Fazendo orixás: sobre o modo de existência das coisas no candomblé”. Religião e Sociedade, Rio de Janeiro, 38 (2), 2018, p. 231.

[2] GONZALES, Lélia. “A categoria político-cultural de amefricanidade”. Tempo Brasileiro, Rio de Janeiro, n. 92/93, 1988, p. 77.

/

Thermal sensation

By expanding their poetics through fabrications of beings that can be assimilated as landscapes, zoomorphic figures, food, trans-species entities, and manifestations of dreamt memorabilia, Diambe (Rio de Janeiro, 1993) reveres the effervescent inventiveness that responds to the blemishes and barriers imposed on dissident bodies in contemporary times. In their creative process, they materialize creatures that inhabit a powerful and autonomous nature, whose power surpasses that of humans and provides an escape from an illusory situation of anthropocentric domination. Simultaneously, in the current exhibition, Diambe discusses how cultures, in different geographical contexts, consider the local temperature as a determining factor in the choice of materials for their objects, addressing the asymmetry in the reciprocity of sociocultural reception established by the African diaspora in Brazil.

In Thermal sensation, a materialization of a perpetual dream ignited by Diambe, paintings with warm chromatic choices, dripped bronze sculptures with colored patinas, and raw clay bases that crack in response to time are presented. The works exhibited on this occasion were produced at a critical moment of environmental temperature in early 2024, with a thermal sensation above 60 degrees Celsius in some cities in southeastern Brazil. Air and fire were kindred. The scorching heat crossed not only the material but also the subjectivity set on fire in the establishment of delirium poetics. The drops of sweat run down the dancing body. The warm saliva that receives the fresh water. The juice of the bitten fruit colors the chin and runs down the open chest.

In this context of astonishing fervor, the transport of the wax sculptures from Diambe's studio to the metal foundry became critical: the bodies melted, disassembled, metamorphosed in response to the blazing heatwave. This torpor also caused a zone of lack of control, setting disobedient limits over the manipulation of the beeswax that shapes the sculptures. Thus, Diambe does not have total plastic authority over the material but respects its own agency, its vital multiplicity, and its delirious possibilities of behavior. From a profound intimacy with the plastic elements, they congregate around the heat a collaborative relationship with the materials, always in synergistic work and mutual action.

After the molds were made, receptacles that would transfer their forms and entities to the incandescent bronze, the wax beings returned from the foundry to Diambe in pieces, soon melted down again to embody other subjectivities and produce new sculptures with the same material, already impregnated with so many cycles of life and death. On the eleventh floor of a building in the center of São Paulo - full of fruits, vegetables, and roots harvested in the Atlantic Forest, the Amazon rainforest, or traded in markets in Benin - the aroma exuded by the beeswax reheated by Diambe often attracted a small swarm that cyclically returned, in a trance, to the material it had created. The preparation of new bodies triggered a call to the beings that produced that plastic mass, in a reunion at the moment of material transformation. This ecological cyclical flow suggests, moreover, a harmonious and sustainable way of dealing with matter, in constant mutation.

Despite the poetic powers of heat, Diambe also alerts to climate exiles and environmental racism, denouncing that the changes caused by global warming affect more voraciously people with dissident bodies and marginalized social groups. Their artistic practice has been permeated by temperature since they set fire to public monuments that revere totalitarian icons that, even static, continue to violate bodies and corrode histories. Heat, on the other hand, also serves as an analogy to the social entropy caused by systems that maintain predatory colonialist and imperialist dynamics.

By merging bodies from different biological and spiritual realms, Diambe incorporates hybrid entities that challenge categorization and encourage more respectful relationships in a nature that can be applied to social spheres. Being a Black person, disobedient to gender binarism, Diambe understands the body as place and place as body, in a mirrored geography that is always political: “the settlement (also called ibá) in candomblé is, at the same time, the dwelling of the orixá, the orixá itself materialized, and the place where the relationship between person and orixá takes place” [1]. Their egg tempera paintings take up the origins of the ancient technique from northeast Africa, finding themselves in the indeterminacy between figurative landscapes, surrealist beings, chromatic abstractions, and other myriad possibilities of existence. Their works are deliberately set in a threshold zone, unnegotiably hybrid, amalgamating natural and metaphysical realms.

With respect to the individuality of the beings they create and places in the universe, Diambe chooses that their bronze cast sculptures be unique, with no other editions. In this way, they obey ancestral epistemologies that understand creation - artistic, in this case, but also of any other nature - as a provider of agency, endowing a being with a body and integrating it into natural dynamics as individuals who, although autonomous, do not exist without harmonious communities of cooperation.

Through knowledge systems from the African diaspora and Amefrican [2] traditions, Diambe's creations and embodiments relate to the notion of food, of offering, as fuel for the body and soul. Eating is, therefore, exercising one's own divinity and that of food, radiating energy, pleasure, happiness, and joy of living. Offering this to the world encompasses expanded notions of time by creating entities that, placed in this banquet-crossroads, will last much longer than their own body, than the molded vegetables that constitute parts of the sculptures, and then the egg used to preserve the vivacity of the pigments in the tempera. By recognizing the perishability of their own body, Diambe dreams of a more enduring offering in temporalities that exceed certain notions of life.

Notes

[1] MARQUES, Lucas. “Fazendo orixás: sobre o modo de existência das coisas no candomblé”. Religião e Sociedade, Rio de Janeiro, 38 (2), 2018, p. 231.

[2] GONZALES, Lélia. “A categoria político-cultural de amefricanidade”. Tempo Brasileiro, Rio de Janeiro, n. 92/93, 1988, p. 77.

Texto originalmente publicado na exposição “Sensação térmica” na galeria Simões de Assis, em São Paulo, de 25 de maio a 20 de julho de 2024.

Galeria Simões de Assis, São Paulo

A expandir sua poética através de fabulações de seres que podem ser assimilados como paisagens, figuras zoomórficas, alimentos, entidades trans-espécies e manifestações de uma memorabilia sonhada, Diambe (Rio de Janeiro, 1993) reverencia a inventividade efervescente que responde a máculas e muralhas impostas a corpos dissidentes na contemporaneidade. Em seu processo criativo, materializa criaturas que habitam uma natureza poderosa e autônoma, cujo poder sobrepuja o do ser humano e proporciona um escape de uma ilusória situação de dominação antropocêntrica. Paralelamente, na presente exposição, Diambe discute como culturas, em diversos contextos geográficos, consideram a temperatura local como fator determinante na escolha dos materiais a comporem seus objetos, endereçando a assimetria na reciprocidade de recepção sociocultural estabelecida pela diáspora africana no Brasil.

Em Sensação térmica, materialização de um sonho perpétuo ignizado por Diambe, apresentam-se pinturas que manifestam escolhas cromáticas calorosas, esculturas gotejadas em bronze com pátinas coloridas e bases de argila crua que racham em resposta ao tempo. As obras expostas nessa ocasião foram produzidas em um momento crítico de temperatura ambiental no início de 2024, com sensação térmica maior que 60 graus Celsius em algumas cidades do sudeste brasileiro. Ar e fogo confundiam-se. O calor alucinante atravessava não somente a matéria, mas a subjetividade posta em fogo no estabelecimento de uma poética do delírio. As gotas de suor que escorrem pelo corpo dançante. A saliva morna que recebe a água fresca. O suco da fruta mordida que colore o queixo e escorre pelo peito aberto.

Nesse contexto de assombroso fervor, o transporte das esculturas em cera do ateliê de Diambe para a fundição em metal tornou-se crítico: os corpos derretiam, desmontavam, metamorfoseavam-se em resposta à fulminante onda de calor. Esse torpor também causa uma zona de descontrole, estabelecendo limites desobedientes sobre a manipulação da cera de abelha que molda as esculturas. Desse modo, Diambe não detém total autoridade plástica sobre a matéria, mas respeita sua própria agência, sua multiplicidade vital e suas delirantes possibilidades de comportamento. A partir de profunda intimidade com os elementos plásticos, congrega em torno do calor uma relação colaborativa com os materiais, sempre em trabalho sinérgico e ação mútua.

Depois de confeccionados os moldes, receptáculos que transfeririam suas formas e entidades ao bronze incandescente, os seres em cera retornavam da oficina de fundição a Diambe em pedaços, logo derretidos novamente para corporificar outras subjetividades e produzir novas esculturas com o mesmo material, já impregnado de tantos ciclos de vida e morte. No décimo primeiro andar de um edifício no centro de São Paulo – repleto de frutos, vegetais e raízes colhidas na Mata Atlântica, na floresta amazônica ou negociadas em mercados no Benin –, o aroma que exalava da cera de abelha reaquecida por Diambe atraía frequentemente um pequeno enxame que retornava, em transe, ciclicamente à matéria que havia criado. A preparação de novos corpos desencadeava um chamado aos seres que produziram aquela massa plástica, em um reencontro no momento da transformação material. Esse ecológico fluxo cíclico sugere, inclusive, uma postura harmônica e sustentável de lidar com a matéria, em constante mutação.

Apesar das potências poéticas do calor, Diambe também alerta para os exílios climáticos e o racismo ambiental, a denunciar que as mudanças causadas pelo aquecimento global afetam de forma mais voraz pessoas com corpos dissidentes e grupos sociais marginalizados. Sua prática artística é perpassada pela temperatura desde quando ateava fogo em monumentos públicos que reverenciam ícones totalitaristas que, mesmo estáticos, continuam a violentar corpos e corroer histórias. O calor, por outro lado, também serve como analogia à entropia social causada pelos sistemas que mantêm predatórias dinâmicas colonialistas e imperialistas.

Ao fundir corpos de diferentes âmbitos biológicos e espirituais, Diambe incorpora entidades híbridas que desafiam categorizações e encorajam relações mais respeitosas em uma natureza que pode ser aplicada às esferas sociais. Sendo pessoa negra, desobediente da binariedade de gênero, Diambe entende o corpo como lugar e o lugar como corpo, em uma espelhada geografia sempre política: “o assentamento (também chamado de ibá) no candomblé é, ao mesmo tempo, a morada do orixá, o próprio orixá materializado e o local onde a relação entre pessoa e orixá se faz” [1]. Suas pinturas em têmpera de ovo retomam a origem da técnica milenar originária do nordeste africano, encontrando-se na indeterminação entre paisagens figurativas, seres surrealistas, abstrações cromáticas e outras miríades de possibilidades de existência. Seus trabalhos acontecem propositalmente em uma zona limiar, inegociavelmente híbrida, a amalgamar reinos naturais e metafísicos.

Em respeito à individualidade dos seres que cria e põe no universo, Diambe escolhe que suas esculturas em bronze fundido sejam únicas, sem outras edições. Dessa forma, obedece a epistemologias ancestrais que entendem a criação – artística, nesse caso, mas também de qualquer outra natureza – como provedora de agência, dotando um ser de corpo e integrando-o em dinâmicas naturais como indivíduos que, embora autônomos, não existem sem comunidades harmônicas de cooperação.

Através de sistemas de saberes da diáspora africana e de tradições amefricanas [2], as criações e corporificações de Diambe se relacionam com a noção de alimento, de oferenda, como combustível do corpo e da alma. Comer é, portanto, exercer a sua própria divindade e a do alimento, irradiando energia, prazer, felicidade e alegria de viver. Oferendar isso ao mundo abarca noções dilatadas de tempo ao criar entidades que, postas nesse banquete-encruzilhada, vão durar muito mais tempo que seu próprio corpo, que os vegetais moldados que constituem partes das esculturas e que o ovo utilizado na conservação da vivacidade dos pigmentos na têmpera. Ao reconhecer a perecibilidade do próprio corpo, Diambe sonha em direção a uma oferenda mais duradoura em temporalidades que extrapolam certas noções de vida.

Notas

[1] MARQUES, Lucas. “Fazendo orixás: sobre o modo de existência das coisas no candomblé”. Religião e Sociedade, Rio de Janeiro, 38 (2), 2018, p. 231.

[2] GONZALES, Lélia. “A categoria político-cultural de amefricanidade”. Tempo Brasileiro, Rio de Janeiro, n. 92/93, 1988, p. 77.

/

Thermal sensation

By expanding their poetics through fabrications of beings that can be assimilated as landscapes, zoomorphic figures, food, trans-species entities, and manifestations of dreamt memorabilia, Diambe (Rio de Janeiro, 1993) reveres the effervescent inventiveness that responds to the blemishes and barriers imposed on dissident bodies in contemporary times. In their creative process, they materialize creatures that inhabit a powerful and autonomous nature, whose power surpasses that of humans and provides an escape from an illusory situation of anthropocentric domination. Simultaneously, in the current exhibition, Diambe discusses how cultures, in different geographical contexts, consider the local temperature as a determining factor in the choice of materials for their objects, addressing the asymmetry in the reciprocity of sociocultural reception established by the African diaspora in Brazil.

In Thermal sensation, a materialization of a perpetual dream ignited by Diambe, paintings with warm chromatic choices, dripped bronze sculptures with colored patinas, and raw clay bases that crack in response to time are presented. The works exhibited on this occasion were produced at a critical moment of environmental temperature in early 2024, with a thermal sensation above 60 degrees Celsius in some cities in southeastern Brazil. Air and fire were kindred. The scorching heat crossed not only the material but also the subjectivity set on fire in the establishment of delirium poetics. The drops of sweat run down the dancing body. The warm saliva that receives the fresh water. The juice of the bitten fruit colors the chin and runs down the open chest.

In this context of astonishing fervor, the transport of the wax sculptures from Diambe's studio to the metal foundry became critical: the bodies melted, disassembled, metamorphosed in response to the blazing heatwave. This torpor also caused a zone of lack of control, setting disobedient limits over the manipulation of the beeswax that shapes the sculptures. Thus, Diambe does not have total plastic authority over the material but respects its own agency, its vital multiplicity, and its delirious possibilities of behavior. From a profound intimacy with the plastic elements, they congregate around the heat a collaborative relationship with the materials, always in synergistic work and mutual action.

After the molds were made, receptacles that would transfer their forms and entities to the incandescent bronze, the wax beings returned from the foundry to Diambe in pieces, soon melted down again to embody other subjectivities and produce new sculptures with the same material, already impregnated with so many cycles of life and death. On the eleventh floor of a building in the center of São Paulo - full of fruits, vegetables, and roots harvested in the Atlantic Forest, the Amazon rainforest, or traded in markets in Benin - the aroma exuded by the beeswax reheated by Diambe often attracted a small swarm that cyclically returned, in a trance, to the material it had created. The preparation of new bodies triggered a call to the beings that produced that plastic mass, in a reunion at the moment of material transformation. This ecological cyclical flow suggests, moreover, a harmonious and sustainable way of dealing with matter, in constant mutation.

Despite the poetic powers of heat, Diambe also alerts to climate exiles and environmental racism, denouncing that the changes caused by global warming affect more voraciously people with dissident bodies and marginalized social groups. Their artistic practice has been permeated by temperature since they set fire to public monuments that revere totalitarian icons that, even static, continue to violate bodies and corrode histories. Heat, on the other hand, also serves as an analogy to the social entropy caused by systems that maintain predatory colonialist and imperialist dynamics.

By merging bodies from different biological and spiritual realms, Diambe incorporates hybrid entities that challenge categorization and encourage more respectful relationships in a nature that can be applied to social spheres. Being a Black person, disobedient to gender binarism, Diambe understands the body as place and place as body, in a mirrored geography that is always political: “the settlement (also called ibá) in candomblé is, at the same time, the dwelling of the orixá, the orixá itself materialized, and the place where the relationship between person and orixá takes place” [1]. Their egg tempera paintings take up the origins of the ancient technique from northeast Africa, finding themselves in the indeterminacy between figurative landscapes, surrealist beings, chromatic abstractions, and other myriad possibilities of existence. Their works are deliberately set in a threshold zone, unnegotiably hybrid, amalgamating natural and metaphysical realms.

With respect to the individuality of the beings they create and places in the universe, Diambe chooses that their bronze cast sculptures be unique, with no other editions. In this way, they obey ancestral epistemologies that understand creation - artistic, in this case, but also of any other nature - as a provider of agency, endowing a being with a body and integrating it into natural dynamics as individuals who, although autonomous, do not exist without harmonious communities of cooperation.

Through knowledge systems from the African diaspora and Amefrican [2] traditions, Diambe's creations and embodiments relate to the notion of food, of offering, as fuel for the body and soul. Eating is, therefore, exercising one's own divinity and that of food, radiating energy, pleasure, happiness, and joy of living. Offering this to the world encompasses expanded notions of time by creating entities that, placed in this banquet-crossroads, will last much longer than their own body, than the molded vegetables that constitute parts of the sculptures, and then the egg used to preserve the vivacity of the pigments in the tempera. By recognizing the perishability of their own body, Diambe dreams of a more enduring offering in temporalities that exceed certain notions of life.

Notes

[1] MARQUES, Lucas. “Fazendo orixás: sobre o modo de existência das coisas no candomblé”. Religião e Sociedade, Rio de Janeiro, 38 (2), 2018, p. 231.

[2] GONZALES, Lélia. “A categoria político-cultural de amefricanidade”. Tempo Brasileiro, Rio de Janeiro, n. 92/93, 1988, p. 77.

Texto originalmente publicado na exposição “Sensação térmica” na galeria Simões de Assis, em São Paulo, de 25 de maio a 20 de julho de 2024.