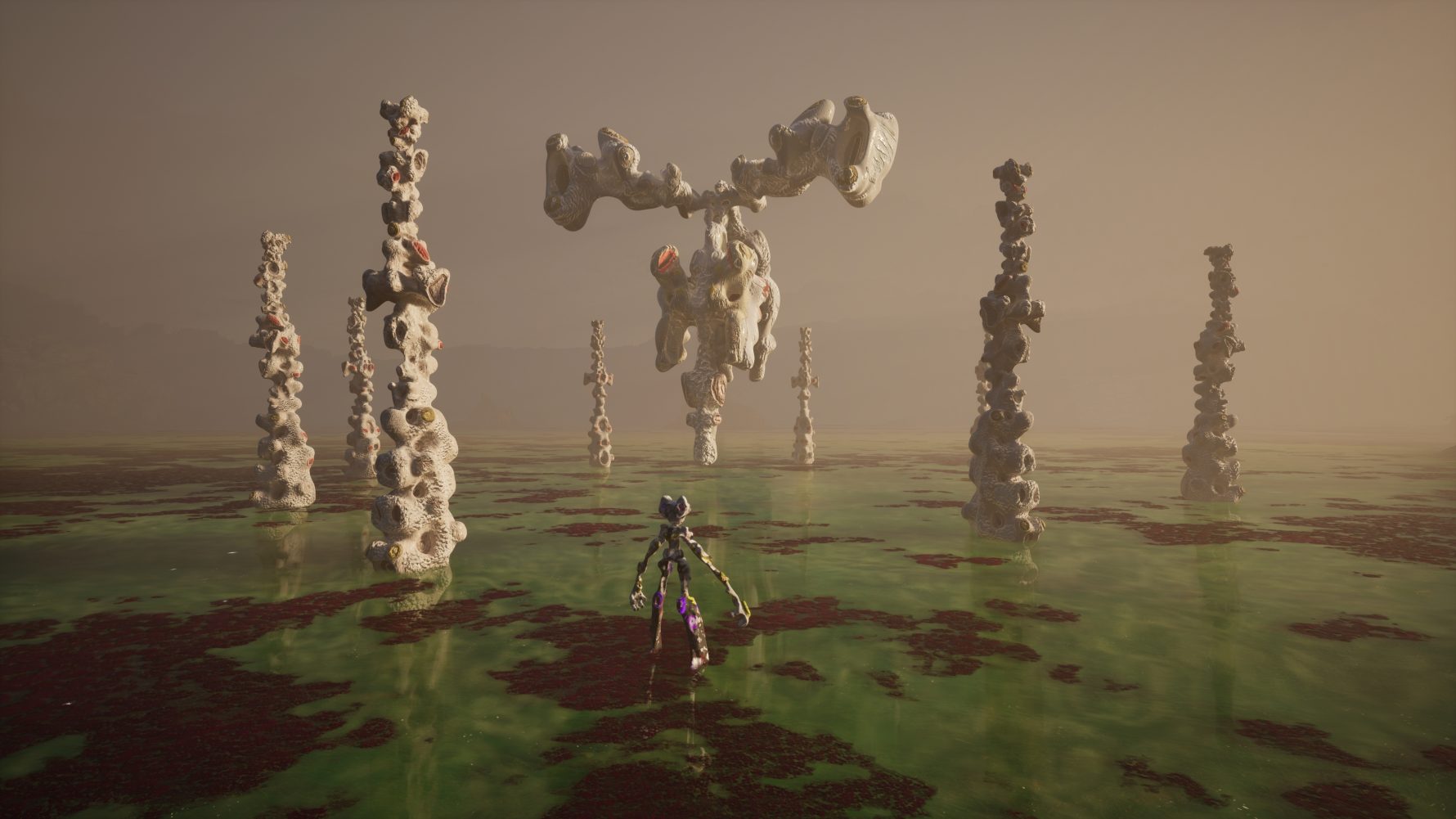

Gabriel Massan & Collaborators, Third World: The Bottom Dimension, 2022 (screenshot).

Gabriel Massan’s immersive afterlives

Gabriel Massan’s star is ascendant in the expanding galaxy of digital art. Born in 1996 and raised on the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro, the Berlin-based artist (currently on a year-long residency in Paris) is indeed what some might call a “digital native”—that increasingly useless appellation. In interviews, Massan recalls a youth spent in Brazilian LAN houses, or cyber cafes, playing games like Second Life. “Everyone was playing GTA or Counter-Strike,” they said. “I was the only queer kid playing The Sims and Second Life.” As a teenager, they started making their own stories, editing together Sims telenovas that earned a cult following on YouTube. More recently, Massan has built their own open worlds to explore the afterlives of Black, Indigenous, and Latinx people. Massan lavishes these worlds with internal contradictions, reframing clashes between natural and digital, erasure and rewriting, and loss and resistance as creative powers. Theirs is a speculative archeology in dialogue with Afrofuturism, Amerindian comprehensions of time, queer ecology, and Saidiya Hartman’s “critical fabulation.”

In Third World: The Bottom Dimension, 2022–23—currently at London’s Serpentine North Gallery and downloadable for free via Steam—players dive headlong into a lush, blaring universe of aerial waterfalls, coralloid structures, and crystalline cyborgs. “I am a species determined by the ephemerality of our goodbyes,” relates one such mysterious entity. “We are not sisters, we are not friends, we are not a family. In fact, what we are could never be said.” The work was made in collaboration with Brazilian artists including Castiel Vitorino Brasileiro, Novíssimo Edgar, and LYZZA. Massan holds the distinction of being the youngest artist to have a solo exhibition at the gallery but betrays little interest in the myth of the preternatural wunderkind or solitary artist-visionary. Rather, they use video games—the art medium that reaches the most people—for revolutionary imagination, evoking a fantastic, colonized unconscious through which dwellers of this “bottom dimension” might eventually dream together and find ways of flourishing in the material world.

Entering this single-player PC game—after clicking on a button that says “Close your mind to start”—one finds that the laws of physics have become undone. Rivers and trees obey different wind flows. Forces of gravity apply varyingly to each body. Waterfalls gush from enormous floating rocks. The bottom dimension abounds with other life-forms: oracles, informants, or mere NPCs with whom the player can dialogue. At the start, a cute, fungiform being welcomes the player into an expedition through the bottom dimension hosted by the “Headquarters”—a fictional company that exploits natural materials from digital worlds. In the game, as IRL, to destroy nature is to destroy life: a core principle from African and Indigenous matrices of thought, neglected by Western culture. Massan channels a tragic lesson learned amid the brutal, rampant dispossession of Indigenous territory under the Bolsonaro regime: that worldbuilding is almost always coincident with planetary ecocide.

As soon as you start exploring, a guide tells you that you are Funfun—a biochemical robot with insectile legs, an amphibian torso, and alien skin like rough gems. Level one, created with Castiel Vitorino Brasileiro, is set in a land called Igba Tingbo (in Yoruba, this can signify both “forest” and “future”) divided into the regions of Tiuí, Nlu, and Domī. The mission: to locate and extract two precious elements, the “Bag of Infinite Seeds” and the “Air Artifice.” By doing so, the ecosystem’s habitability will become violently disrupted. Later, in Sòfo (which stands for “emptiness” in Yoruba), an ecosystem built with Novíssimo Edgar, you play as Buburu. Anthropomorphic like Funfun but with a stockier body, an antenna, and a silvery exoskeleton, Buburu quests for elements like the “Crystal of Life.” The various bosses of the bottom dimension—among them a barking monster who resembles Super Mario’s Bowser on steroids—try to defend these valuable assets and establish healing processes. By having players uproot natural resources and spiritual foundations, Massan hopes to generate solidarity with the real-life victims of Brazil’s horrific extractivismo.

Massan also recasts the binaries of how we interact with an artwork—author and reader, developer and player, artist and viewer—as ambiguous and tangled fluxes. What distinguishes Third World from most other open-world video games is the epistemological provocation to overflow the game and to burst into society, to rewrite history collectively. By finding insignias with a camera icon, a player can enter into “capture mode,” where it’s possible to mint in-game memories into NFTs with the blockchain platform Tezos, building a public archive of fifteen-second videos or snapshots that store perspectives that would otherwise gradually vanish, as testimonies and oral stories from oppressed groups. (That these consciousness-raising images and meanings are merged into a bank of collectible cryptocurrency is an irony perhaps unintended by the artist.)

In their 2022 video Don’t Say Goodbye to Earth, showcased in the Bangkok Biennale Online Pavilion, Massan revisits traumatic moments in which they witnessed the deaths of family members. Over undulant, multicolored pools of water and light, the artist composes a moving exequy around which glistening entities ethereally float and spiral, flanked by protective priestesses and mournful healers in prayer who wake the body in its transmutation. In doing so, Massan recreates more beautiful, honorable funerals for the people they lost: a grandmother, a cousin, a friend. The work reminds us that the erasure of death rituals and other traditions around the passage of life was and remains a brutal weapon used by colonialism in the oppression of enslaved and marginalized people. The temporal shuffling of Don’t Say Goodbye to Earth—a sequence of lingering close-ups and ambiguous reverse shots, at once intensely intimate and alien—is aligned with the Yoruba cosmovision of candomblé, which understands ancestry as an ongoing exchange between past and present.

The elastic morphology of Massan’s digital sculptures extends to time itself. When your character dies in Third World, a question appears—“Have you seen everything?”—with a Yes/No choice. By clicking “No,” you come back to a safe place near where you died. Death, therefore, is not an end, but a moment of reflection that boomerangs time. While nonlinearity and the ability to respawn are nothing new in video games, the many afterlives of Third World seem to collectively advance a hopeful assertion about existence on Earth: We have not seen everything yet.

Texto originalmente publicado na Artforum, em 9 de outubro de 2023

Gabriel Massan’s star is ascendant in the expanding galaxy of digital art. Born in 1996 and raised on the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro, the Berlin-based artist (currently on a year-long residency in Paris) is indeed what some might call a “digital native”—that increasingly useless appellation. In interviews, Massan recalls a youth spent in Brazilian LAN houses, or cyber cafes, playing games like Second Life. “Everyone was playing GTA or Counter-Strike,” they said. “I was the only queer kid playing The Sims and Second Life.” As a teenager, they started making their own stories, editing together Sims telenovas that earned a cult following on YouTube. More recently, Massan has built their own open worlds to explore the afterlives of Black, Indigenous, and Latinx people. Massan lavishes these worlds with internal contradictions, reframing clashes between natural and digital, erasure and rewriting, and loss and resistance as creative powers. Theirs is a speculative archeology in dialogue with Afrofuturism, Amerindian comprehensions of time, queer ecology, and Saidiya Hartman’s “critical fabulation.”

In Third World: The Bottom Dimension, 2022–23—currently at London’s Serpentine North Gallery and downloadable for free via Steam—players dive headlong into a lush, blaring universe of aerial waterfalls, coralloid structures, and crystalline cyborgs. “I am a species determined by the ephemerality of our goodbyes,” relates one such mysterious entity. “We are not sisters, we are not friends, we are not a family. In fact, what we are could never be said.” The work was made in collaboration with Brazilian artists including Castiel Vitorino Brasileiro, Novíssimo Edgar, and LYZZA. Massan holds the distinction of being the youngest artist to have a solo exhibition at the gallery but betrays little interest in the myth of the preternatural wunderkind or solitary artist-visionary. Rather, they use video games—the art medium that reaches the most people—for revolutionary imagination, evoking a fantastic, colonized unconscious through which dwellers of this “bottom dimension” might eventually dream together and find ways of flourishing in the material world.

Entering this single-player PC game—after clicking on a button that says “Close your mind to start”—one finds that the laws of physics have become undone. Rivers and trees obey different wind flows. Forces of gravity apply varyingly to each body. Waterfalls gush from enormous floating rocks. The bottom dimension abounds with other life-forms: oracles, informants, or mere NPCs with whom the player can dialogue. At the start, a cute, fungiform being welcomes the player into an expedition through the bottom dimension hosted by the “Headquarters”—a fictional company that exploits natural materials from digital worlds. In the game, as IRL, to destroy nature is to destroy life: a core principle from African and Indigenous matrices of thought, neglected by Western culture. Massan channels a tragic lesson learned amid the brutal, rampant dispossession of Indigenous territory under the Bolsonaro regime: that worldbuilding is almost always coincident with planetary ecocide.

As soon as you start exploring, a guide tells you that you are Funfun—a biochemical robot with insectile legs, an amphibian torso, and alien skin like rough gems. Level one, created with Castiel Vitorino Brasileiro, is set in a land called Igba Tingbo (in Yoruba, this can signify both “forest” and “future”) divided into the regions of Tiuí, Nlu, and Domī. The mission: to locate and extract two precious elements, the “Bag of Infinite Seeds” and the “Air Artifice.” By doing so, the ecosystem’s habitability will become violently disrupted. Later, in Sòfo (which stands for “emptiness” in Yoruba), an ecosystem built with Novíssimo Edgar, you play as Buburu. Anthropomorphic like Funfun but with a stockier body, an antenna, and a silvery exoskeleton, Buburu quests for elements like the “Crystal of Life.” The various bosses of the bottom dimension—among them a barking monster who resembles Super Mario’s Bowser on steroids—try to defend these valuable assets and establish healing processes. By having players uproot natural resources and spiritual foundations, Massan hopes to generate solidarity with the real-life victims of Brazil’s horrific extractivismo.

Massan also recasts the binaries of how we interact with an artwork—author and reader, developer and player, artist and viewer—as ambiguous and tangled fluxes. What distinguishes Third World from most other open-world video games is the epistemological provocation to overflow the game and to burst into society, to rewrite history collectively. By finding insignias with a camera icon, a player can enter into “capture mode,” where it’s possible to mint in-game memories into NFTs with the blockchain platform Tezos, building a public archive of fifteen-second videos or snapshots that store perspectives that would otherwise gradually vanish, as testimonies and oral stories from oppressed groups. (That these consciousness-raising images and meanings are merged into a bank of collectible cryptocurrency is an irony perhaps unintended by the artist.)

In their 2022 video Don’t Say Goodbye to Earth, showcased in the Bangkok Biennale Online Pavilion, Massan revisits traumatic moments in which they witnessed the deaths of family members. Over undulant, multicolored pools of water and light, the artist composes a moving exequy around which glistening entities ethereally float and spiral, flanked by protective priestesses and mournful healers in prayer who wake the body in its transmutation. In doing so, Massan recreates more beautiful, honorable funerals for the people they lost: a grandmother, a cousin, a friend. The work reminds us that the erasure of death rituals and other traditions around the passage of life was and remains a brutal weapon used by colonialism in the oppression of enslaved and marginalized people. The temporal shuffling of Don’t Say Goodbye to Earth—a sequence of lingering close-ups and ambiguous reverse shots, at once intensely intimate and alien—is aligned with the Yoruba cosmovision of candomblé, which understands ancestry as an ongoing exchange between past and present.

The elastic morphology of Massan’s digital sculptures extends to time itself. When your character dies in Third World, a question appears—“Have you seen everything?”—with a Yes/No choice. By clicking “No,” you come back to a safe place near where you died. Death, therefore, is not an end, but a moment of reflection that boomerangs time. While nonlinearity and the ability to respawn are nothing new in video games, the many afterlives of Third World seem to collectively advance a hopeful assertion about existence on Earth: We have not seen everything yet.

Texto originalmente publicado na Artforum, em 9 de outubro de 2023

Gabriel Massan & Collaborators, Third World: The Bottom Dimension, 2022 (screenshot).

Gabriel Massan & Collaborators, Third World: The Bottom Dimension, 2022 (screenshot).

Gabriel Massan, Don’t Say Goodbye to Earth, 2022 (screenshot).