Gustavo Rezende, Maxwell chegando com cachorro, 2011. Fotos EstudioEmObra.

2022. Gustavo Rezende

Exposição “Dentro de mim, não me vejo”

Texto crítico para a exposição da VERVE, na ArPa 2022, em São Paulo

Texto crítico para a exposição da VERVE, na ArPa 2022, em São Paulo

Dentro de mim, não me vejo

Paris, 1889. A torre Eiffel havia sido há pouco inaugurada. A construção dividia opiniões: alguns a admiravam como símbolo de progresso francês, enquanto outros relutavam com a gigantesca torre erigida em um rompante na paisagem da cidade. O poeta francês Guy de Maupassant era um dos opositores ao projeto: entretanto, durante longo período, almoçava todos os dias em um dos restaurantes do primeiro piso da torre de ferro. Quando indagado sobre essa aparente contradição, respondia que aquele era o único lugar de Paris em que podia estar e não ver a torre.

A recente produção do artista Gustavo Rezende parece aproximar-se, em muitos pontos, a essa estória. A repetida produção de esculturas que retratam Maxwell, personagem que se apresenta como espécie de alter ego do artista, não recai em um ato ensimesmado ou numa repetição narcísica. Constitui, porém, um sólido corpo de trabalho que objetiva atacar questões próprias ao campo da história e da teoria da arte contemporânea, sem negligenciar os contributos da modernidade para o âmbito da escultura. Dessa forma, dentro de si mesmo é o único lugar de onde não se vê: adotando sua fisionomia individual como principal ferramenta ilustrativa da narrativa, o artista pode, enfim, abandonar esse tema e deter-se a questões es- sencialmente intelectuais, artísticas e escultóricas.

As indagações de Rezende sobre o posicionamento do artista na contemporaneidade versam – entre muitos outros assuntos – sobre a dualidade do interno e do externo, indivíduo e do coletivo, da visão de si mesmo e dos outros. Apenas pela visão no ângulo em que são exibidas, não se distingue se as esculturas do artista são ocas ou maciças, mais valendo o que o espectador acredita que elas sejam. Num ar próximo ao ceticismo filosófico, incisivamente discutido em seus trabalhos, especialmente no final da década de 1990, o artista levanta questionamentos contundentes sobre a aparência e a essência – ou a casca e o miolo –, princípios caros à técnica da escultura, sobretudo acerca de si mesmo. Esses pontos cruciais são direcionados por Rezende a uma discussão meta-artística, que concerne muito mais a questões teóricas sobre a arte do que questões existenciais individuais.

As investigações de Rezende proporcionaram-no um alargamento quanto ao repertório imagético e um aprofundamento quanto ao arcabouço teórico, causando um confrontamento do artista com respostas já aparentemente bem solucionadas para questões centrais da prática escultórica. Os diálogos que o artista traça com princípios modernos – como a cor sólida, a reprodutibilidade e o monólito como proposta de algo puro – e contemporâneos – como possibilidades geográficas da escultura, a impressão de movimento e as possíveis relações da escultura com uma base – aparentam uma inquietude questionadora em um panorama em que muito já foi dito, mas não o suficiente. A inesgotabilidade do assunto, ao mesmo tempo que o conforta, o assola; mas, no final das contas, a insatisfação o basta.

No recorte de trabalhos expostos nessa ocasião, há uma dicotômica latência que Rezende explora há décadas. Primeiramente, uma potencialidade poética – fabulada tradicionalmente pelo artista ao definir seus títulos enigmáticos, principalmente em seus trabalhos mais antigos –, acentuada por uma narrativa fictícia atrelada à figuração, provocando no espectador a necessidade da elaboração de um raconto que não é oficializado pelo artista – às vezes, inclusive, por não existir. Em um segundo momento, há uma contingência de movimento característica em suas esculturas, em uma oscilação entre o bidimensional – especialmente nos relevos – e o tridimensional – nas obras de maior profundidade. O desenvolvimento poético e plástico

de Rezende se configura robusto ao mesmo passo que se faz paradoxal, com assertivos enigmas: uma suposta “facilidade de compreensão” da sua obra pela conexão familiar que se tem com o aspecto figurativo humano se esvai no segundo em que embrenha, mesmo que superficialmente, no universo intelectual do artista.

A fisionomia das esculturas tomou a sua própria por coincidência do destino. A torre Eiffel também não tinha intencionalmente esse nome: roubou o nome do seu criador, Gustave Eiffel, por conveniência. Frankenstein também não é o nome da criatura, como nos é automático, mas do doutor que o criou. Esse fenômeno geralmente acontece quando a obra se torna maior que seu criador, extrapolando os limites individuais e analisando os contributos ideológicos para um contexto mais expandido. Essa é uma das maneiras pelas quais podemos ler a espelhada obra de Gustavo Rezende.

/

Inside me, I can’t see myself

Paris, 1889. The Eiffel Tower had just been inaugurated. The construction divided opinions: some admired it as a symbol of French progress, while others were reluctant to have the gigantic tower erected in a burst in the city’s landscape. The French poet Guy de Maupassant was one of the main project’s opponents: however, for a long time, he had lunch every single day in one of the restaurants on the first floor of the iron tower. When asked about this apparent contradiction, he replied that it was the only place in Paris where he could be and not see the tower.

The recent production of the artist Gustavo Rezende seems to come close, in many points, to this story. The repeated production of sculptures that portray Maxwell, a character who presents himself as a kind of alter ego of the artist, does not fall into a self-absorbed act or a narcissistic repetition. It constitutes, however, a solid body of work that aims to tackle questions specific to the field of history and theory of contemporary art, without neglecting the contributions of modernity to the sphere of sculpture. In this way, inside himself is the only place from wheere he cannot be seen: by adopting his individual physiognomy as the main illustrative tool of the narrative, the artist can, finally, abandon this theme and focus at essentially intellectual, artistic and sculptural questions.

Rezende’s inquiries about the artist’s positioning in contemporary times deal – among many other subjects – with the duality of the internal and the external, the individual and the collective, the vision of himself and others. Just by looking at the angle at which they are displayed, it is not possible to distinguish whether the artist’s sculptures are hollow or massive, rather what the spectator believes them to be. In an air close to philosophical skepticism, incisively discussed in his works especially in the late 1990s, the artist raises strong questions about appearance and essence – or the shell and the core –, principles dear to the technique of sculpture, especially about himself. These crucial points are addressed by Rezende to a meta-artistic discussion, which concerns a lot more theoretical questions about art than individual existential questions.

Rezende’s investigations provided him with a broadening of his imagery repertoire and a deepening of his theoretical framework, causing the artist to confront himself with already apparently well-resolved answers to central questions of the sculptural practice. The dialogues that the artist traces with modern principles – such as solid color, reproducibility and the monolith as a proposal for something pure – and contemporary ones – such as the geographical possibilities of sculpture, the impression of move- ment and the possible relationships of the sculpture with a base

– showcase a questioning restlessness in a panorama in which much has already been said, but not enough. The inexhaustibility of the subject, at the same time that comforts him, ravages him; but in the end, dissatisfaction is enough.

In the selection of works exhibited on this occasion, there is a dichotomous latency that Rezende has been exploring for decades. First, a poetic potentiality – traditionally fabled by the artist when defining his enigmatic titles, especially in his early works –, accentuated by a fictional narrative linked to figuration, provoking the need for the spectator to elaborate a tale that is not officialized by the artist – sometimes even because it doesn’t exist. In a second moment, there is a contingency of movement characteristic in his sculptures, in an oscillation between the two-dimensional – especially in the relief sculptures – and the three-dimensional – in the works of greater depth. Rezende’s poetic and plastic development is robust at the same time as it becomes paradoxical, with assertive enigmas: a supposed “ease of understanding” of his work due to the acquainted connection that one has with the human figurative aspect disappears the second of entering, even if superficially, in the artist’s intellectual universe.

The physiognomy of the sculptures took his own by coincidence. The Eiffel Tower was also not intentionally named this way: it stole the name of its creator, Gustave Eiffel, for convenience. Frankenstein is also not the name of the creature, as is automatic for us, but of the doctor who created him. This phenomenon usually happens when the work becomes bigger than its creator, extrapolating individual limits and analyzing ideological contributions to a broader context. This is one of the ways in which we can read the mirrored work of Gustavo Rezende.

Texto originalmente publicado na exposição “Dentro de mim, não me vejo” da VERVE na ArPa 2022, de 1 a 5 de junho de 2022

Paris, 1889. A torre Eiffel havia sido há pouco inaugurada. A construção dividia opiniões: alguns a admiravam como símbolo de progresso francês, enquanto outros relutavam com a gigantesca torre erigida em um rompante na paisagem da cidade. O poeta francês Guy de Maupassant era um dos opositores ao projeto: entretanto, durante longo período, almoçava todos os dias em um dos restaurantes do primeiro piso da torre de ferro. Quando indagado sobre essa aparente contradição, respondia que aquele era o único lugar de Paris em que podia estar e não ver a torre.

A recente produção do artista Gustavo Rezende parece aproximar-se, em muitos pontos, a essa estória. A repetida produção de esculturas que retratam Maxwell, personagem que se apresenta como espécie de alter ego do artista, não recai em um ato ensimesmado ou numa repetição narcísica. Constitui, porém, um sólido corpo de trabalho que objetiva atacar questões próprias ao campo da história e da teoria da arte contemporânea, sem negligenciar os contributos da modernidade para o âmbito da escultura. Dessa forma, dentro de si mesmo é o único lugar de onde não se vê: adotando sua fisionomia individual como principal ferramenta ilustrativa da narrativa, o artista pode, enfim, abandonar esse tema e deter-se a questões es- sencialmente intelectuais, artísticas e escultóricas.

As indagações de Rezende sobre o posicionamento do artista na contemporaneidade versam – entre muitos outros assuntos – sobre a dualidade do interno e do externo, indivíduo e do coletivo, da visão de si mesmo e dos outros. Apenas pela visão no ângulo em que são exibidas, não se distingue se as esculturas do artista são ocas ou maciças, mais valendo o que o espectador acredita que elas sejam. Num ar próximo ao ceticismo filosófico, incisivamente discutido em seus trabalhos, especialmente no final da década de 1990, o artista levanta questionamentos contundentes sobre a aparência e a essência – ou a casca e o miolo –, princípios caros à técnica da escultura, sobretudo acerca de si mesmo. Esses pontos cruciais são direcionados por Rezende a uma discussão meta-artística, que concerne muito mais a questões teóricas sobre a arte do que questões existenciais individuais.

As investigações de Rezende proporcionaram-no um alargamento quanto ao repertório imagético e um aprofundamento quanto ao arcabouço teórico, causando um confrontamento do artista com respostas já aparentemente bem solucionadas para questões centrais da prática escultórica. Os diálogos que o artista traça com princípios modernos – como a cor sólida, a reprodutibilidade e o monólito como proposta de algo puro – e contemporâneos – como possibilidades geográficas da escultura, a impressão de movimento e as possíveis relações da escultura com uma base – aparentam uma inquietude questionadora em um panorama em que muito já foi dito, mas não o suficiente. A inesgotabilidade do assunto, ao mesmo tempo que o conforta, o assola; mas, no final das contas, a insatisfação o basta.

No recorte de trabalhos expostos nessa ocasião, há uma dicotômica latência que Rezende explora há décadas. Primeiramente, uma potencialidade poética – fabulada tradicionalmente pelo artista ao definir seus títulos enigmáticos, principalmente em seus trabalhos mais antigos –, acentuada por uma narrativa fictícia atrelada à figuração, provocando no espectador a necessidade da elaboração de um raconto que não é oficializado pelo artista – às vezes, inclusive, por não existir. Em um segundo momento, há uma contingência de movimento característica em suas esculturas, em uma oscilação entre o bidimensional – especialmente nos relevos – e o tridimensional – nas obras de maior profundidade. O desenvolvimento poético e plástico

de Rezende se configura robusto ao mesmo passo que se faz paradoxal, com assertivos enigmas: uma suposta “facilidade de compreensão” da sua obra pela conexão familiar que se tem com o aspecto figurativo humano se esvai no segundo em que embrenha, mesmo que superficialmente, no universo intelectual do artista.

A fisionomia das esculturas tomou a sua própria por coincidência do destino. A torre Eiffel também não tinha intencionalmente esse nome: roubou o nome do seu criador, Gustave Eiffel, por conveniência. Frankenstein também não é o nome da criatura, como nos é automático, mas do doutor que o criou. Esse fenômeno geralmente acontece quando a obra se torna maior que seu criador, extrapolando os limites individuais e analisando os contributos ideológicos para um contexto mais expandido. Essa é uma das maneiras pelas quais podemos ler a espelhada obra de Gustavo Rezende.

/

Inside me, I can’t see myself

Paris, 1889. The Eiffel Tower had just been inaugurated. The construction divided opinions: some admired it as a symbol of French progress, while others were reluctant to have the gigantic tower erected in a burst in the city’s landscape. The French poet Guy de Maupassant was one of the main project’s opponents: however, for a long time, he had lunch every single day in one of the restaurants on the first floor of the iron tower. When asked about this apparent contradiction, he replied that it was the only place in Paris where he could be and not see the tower.

The recent production of the artist Gustavo Rezende seems to come close, in many points, to this story. The repeated production of sculptures that portray Maxwell, a character who presents himself as a kind of alter ego of the artist, does not fall into a self-absorbed act or a narcissistic repetition. It constitutes, however, a solid body of work that aims to tackle questions specific to the field of history and theory of contemporary art, without neglecting the contributions of modernity to the sphere of sculpture. In this way, inside himself is the only place from wheere he cannot be seen: by adopting his individual physiognomy as the main illustrative tool of the narrative, the artist can, finally, abandon this theme and focus at essentially intellectual, artistic and sculptural questions.

Rezende’s inquiries about the artist’s positioning in contemporary times deal – among many other subjects – with the duality of the internal and the external, the individual and the collective, the vision of himself and others. Just by looking at the angle at which they are displayed, it is not possible to distinguish whether the artist’s sculptures are hollow or massive, rather what the spectator believes them to be. In an air close to philosophical skepticism, incisively discussed in his works especially in the late 1990s, the artist raises strong questions about appearance and essence – or the shell and the core –, principles dear to the technique of sculpture, especially about himself. These crucial points are addressed by Rezende to a meta-artistic discussion, which concerns a lot more theoretical questions about art than individual existential questions.

Rezende’s investigations provided him with a broadening of his imagery repertoire and a deepening of his theoretical framework, causing the artist to confront himself with already apparently well-resolved answers to central questions of the sculptural practice. The dialogues that the artist traces with modern principles – such as solid color, reproducibility and the monolith as a proposal for something pure – and contemporary ones – such as the geographical possibilities of sculpture, the impression of move- ment and the possible relationships of the sculpture with a base

– showcase a questioning restlessness in a panorama in which much has already been said, but not enough. The inexhaustibility of the subject, at the same time that comforts him, ravages him; but in the end, dissatisfaction is enough.

In the selection of works exhibited on this occasion, there is a dichotomous latency that Rezende has been exploring for decades. First, a poetic potentiality – traditionally fabled by the artist when defining his enigmatic titles, especially in his early works –, accentuated by a fictional narrative linked to figuration, provoking the need for the spectator to elaborate a tale that is not officialized by the artist – sometimes even because it doesn’t exist. In a second moment, there is a contingency of movement characteristic in his sculptures, in an oscillation between the two-dimensional – especially in the relief sculptures – and the three-dimensional – in the works of greater depth. Rezende’s poetic and plastic development is robust at the same time as it becomes paradoxical, with assertive enigmas: a supposed “ease of understanding” of his work due to the acquainted connection that one has with the human figurative aspect disappears the second of entering, even if superficially, in the artist’s intellectual universe.

The physiognomy of the sculptures took his own by coincidence. The Eiffel Tower was also not intentionally named this way: it stole the name of its creator, Gustave Eiffel, for convenience. Frankenstein is also not the name of the creature, as is automatic for us, but of the doctor who created him. This phenomenon usually happens when the work becomes bigger than its creator, extrapolating individual limits and analyzing ideological contributions to a broader context. This is one of the ways in which we can read the mirrored work of Gustavo Rezende.

Texto originalmente publicado na exposição “Dentro de mim, não me vejo” da VERVE na ArPa 2022, de 1 a 5 de junho de 2022

Gustavo Rezende, A Lapa de baixo e a metafísica da dama #4, 2022.

Gustavo Rezende, A Lapa de baixo e a metafísica da dama #1, 2022.

Gustavo Rezende, A Lapa de baixo e a metafísica da dama #2, 2022.

Gustavo Rezende, A Lapa de baixo e a metafísica da dama #3, 2022.

Gustavo Rezende, Qual a matéria dos sonhos?, 2012.

Gustavo Rezende, Maxwell Hustling, 2015.

Gustavo Rezende, Diadorim, 2011.

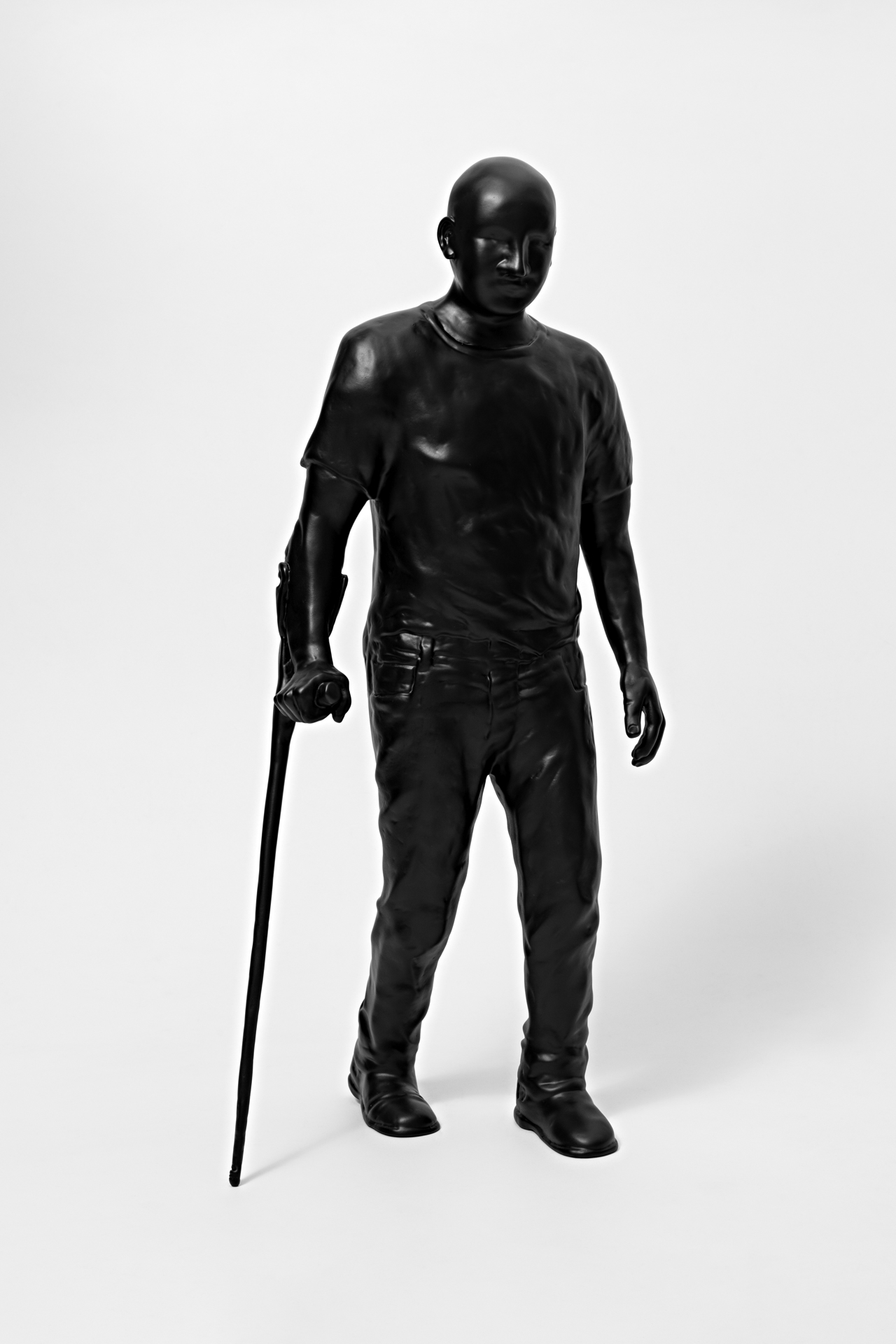

Gustavo Rezende, Maxwell caminhando, 2020.

Gustavo Rezende, Maxwell observando, 2020.

Gustavo Rezende, Maxwell deitado, 2013.

Gustavo Rezende, Maxwell vindo #8, 2021.

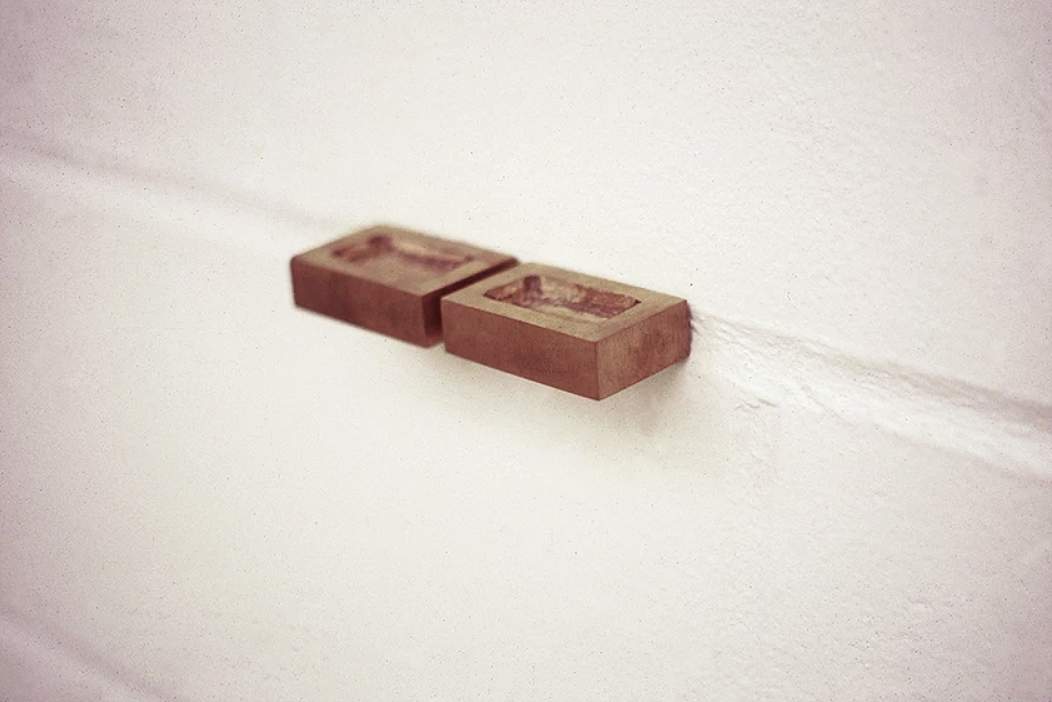

Gustavo Rezende, Two boxes for your blue eyes, 1994.

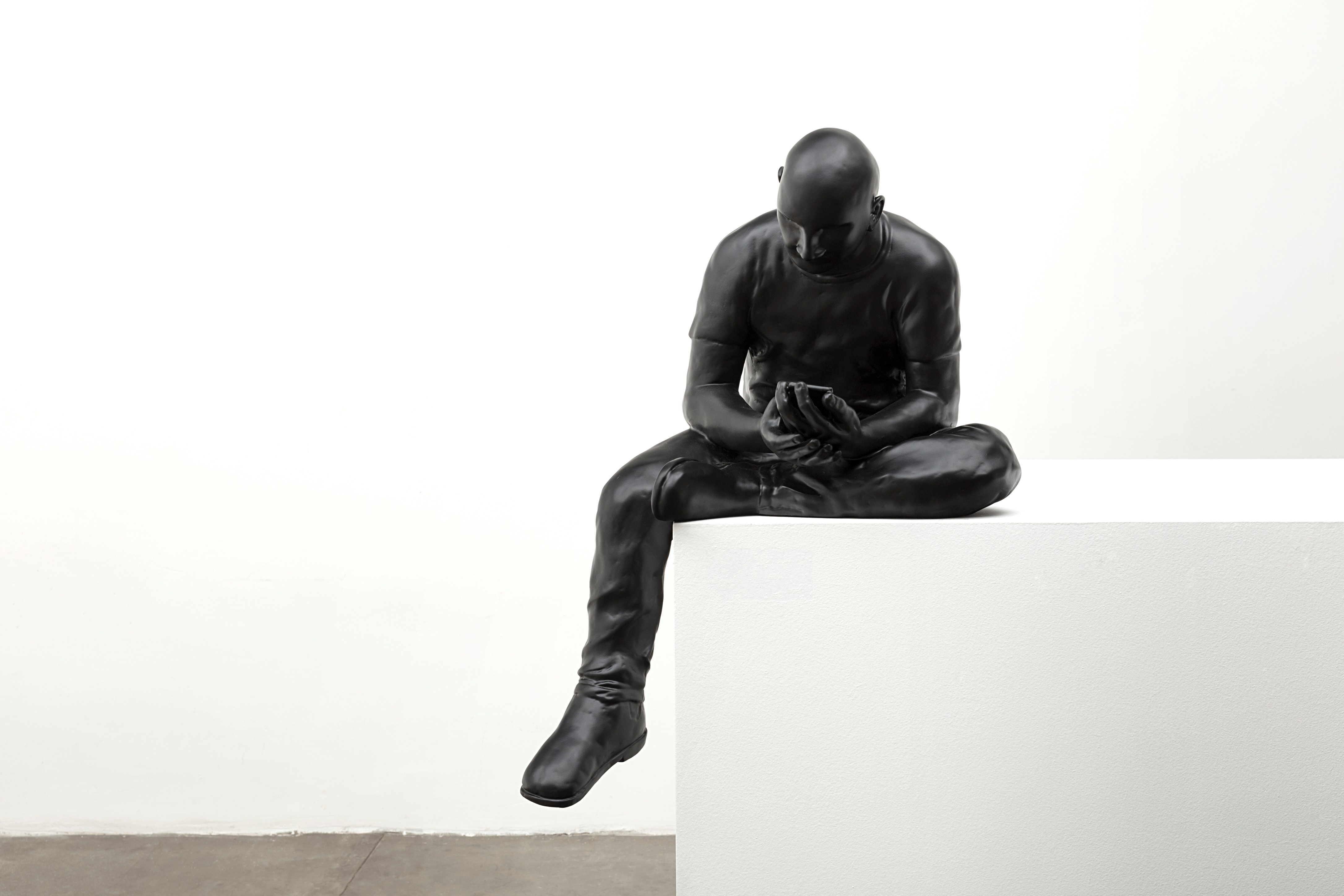

Gustavo Rezende, Maxwell Dwelling, 2020.

Gustavo Rezende, Maxwell vindo #7, 2020.

Gustavo Rezende, Maxwell sentado, 2021.

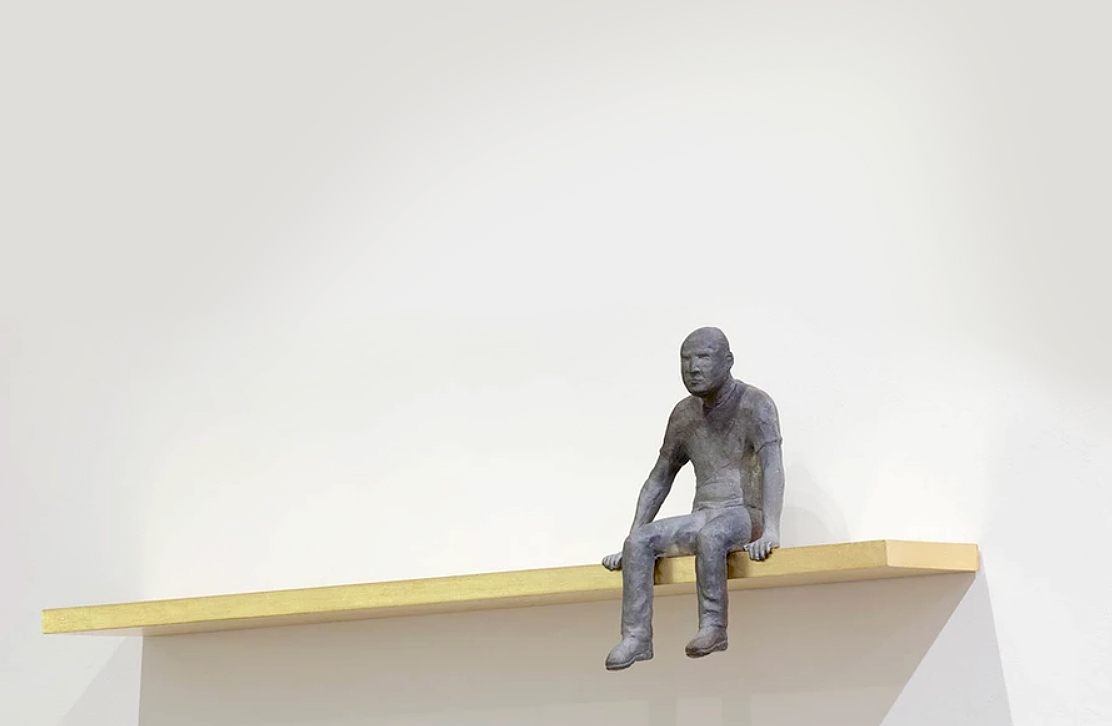

Gustavo Rezende, Maxwell sentado, 2012.

Fotos EstudioEmObra.