Igor Vidor, Animal Ferido, vista da exposição, 2022. Todas as fotos deste artigo são de Bruno Leão.

Lacerated cuirass

Looking from a distance, as in a hunting position, the gallery is surrounded by an earth-colored curtain. At first sight, it is not known whether it is an armor, as a protection of what is kept inside, or an adornment that confers power, like a royal mantle. Maybe inside dwells the animal ferido (“wounded animal”) that entitles the show. Maybe it still needs protection, at the same time it flaunts his comeback.

The Brazilian artist Igor Vidor (São Paulo, 1985) presents a new body of work that deepens his research on violence, crime, politics and instances of power in Brazil. The works can be critically read under the analogous image of the cuirass, or the thickened skin of a wounded animal that has strengthened by being continuously wounded. The argument showcases the duality of the lacerated skin: being a proof of vulnerability that simultaneously grants an element of protection. The artist presents big sculptures made of bulletproof fabric and iron representing allegories of power, sculptures about traffic of drugs and guns, and installations with earth and cloth. Some of the works present bullet shells collected on the streets of Rio de Janeiro in crossfire, reminding that every ammo casing found on the ground is the skin of a materialized attempt to tear down a body. Vidor’s works showcase how the skin can be shattered, trespassed by a bullet, but also be a camouflage, a disguise, a bulletproof vest—or a cuirass made by skinning oppressed people alive by brutal force and using it as a golden fleece.

Animal Ferido is the first solo show by the artist after his 3-year political exile in Germany. Between the two rounds of the Brazilian presidential election that would elect Jair Bolsonaro in 2018, Vidor emphasized through his works the death of marginalized youths and the relationship between drug trafficking, political figures and power structures in Rio de Janeiro. After several death threats to him and his family for his impactful work, opening wide the dynamics of ultraviolence between public security, government institutions and the militias, the artist managed to flee the country in 2019. Vidor was sheltered by the Martin Roth Initiative, a program promoted by Germany’s Institute of Exterior Relations and Goethe Institute, for political protection of artists at risk from all over the globe. After developing his artistic research on residency programs in Europe—as Künstlerhaus Bethanien, in Berlin, and Pro Helvetia South America, in Zurich—, the artist is reestablishing his connections with his homeland, in an optimistic moment of decay of the right-wing conservatism caused by the comeback election of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva for Presidency on the end of last October.

Through the exhibited works, Vidor tries to construct a genealogy of violence from the first related events since the establishment of a republic in Brazil, setting a historic mark since the War of Canudos from 1897—the deadliest civil war in Brazilian history. It happened a year after the abolition of slavery in the country, when an armed combat took place between military and civil forces in northeastern Brazil. Vidor illustrates this narrative with the image of a tree named favela, very common on Canudos, that gave name to a type of urban occupation—close to a ghetto or a slum—that occurs specifically in Brazil. Baptizing these takeover spaces with the name of this plant is a form of resistance and irradiation of defiance.

The curtain that circle the gallery—on the same tone as the soil from Canudos, as the walls are painted with the earth itself—is stamped with handmade drawings of the favela plant and guns used on the war, denouncing how Brazilian flora is merged with a technology expressed through the armamentist production. This relation between an exoticism linked to Brazilian nature—from colonial times, with the naturalist expeditions—and the bestiality that these visual codes confer to a discourse of violence in the country is operated by the artist in his sculptures from the series Alegoria do terror (“Allegory of terror”).

On bulletproof aramid—fabric of which the Brazilian market is one of the top consumers, used in armoring cars and making bulletproof vests—Vidor inserts images by ultraviolet printing, operating symbols that constitute hundreds of badges of military police and special operations researched by the artist. These emblems merge European traditions of heraldry—usually employed on coats of arms—and a certain savagery linked to the Brazilian fauna, consciously referring to tradition and fear. The artist then mixes this arsenal of images with distorted photos of Brazilian Supreme Court members, architectural elements of government buildings, fragments of historic paintings, Portuguese royal jewelry from the Brazilian colonial age, and Viagra pills—believe it or not, 35,000 of them were bought in 2022 by Brazilian Armed Forces with public money under Jair Bolsonaro’s presidency.

The fabric that presents the images is held by an iron structure, as a metaphor that all allegories of violence, meticulously thought out, have a dense warlike backstage behind them. Analogously, Vidor’s criticisms about the incisions made upon the oppressed skin can be read as a clash with Eurocentric artistic tradition that has its main medium as a canvas stretched on a frame, as a skin tensioned over a chassis. While colonialist technology is always appointed to exploitation dynamics, the artist turns the cycle inside out when using the bulletproof fabric made in Europe to support his denunciations to the rooted violence.

For the show, Vidor invited two fellow artists to exhibit their works amongst his: Silvio de Camillis Borges (São Paulo, 1985) and Gilson Plano (Goiânia, 1988). Vidor proposed a narrative that only finds true meaning in collaboration, in the dialogue between combatants of a collective struggle. In the world of contemporary galleries, where artists duel for solo shows and hoist individuality as an ensign, the possibility of collaboration and integration of unrepresented artists is utterly arduous.

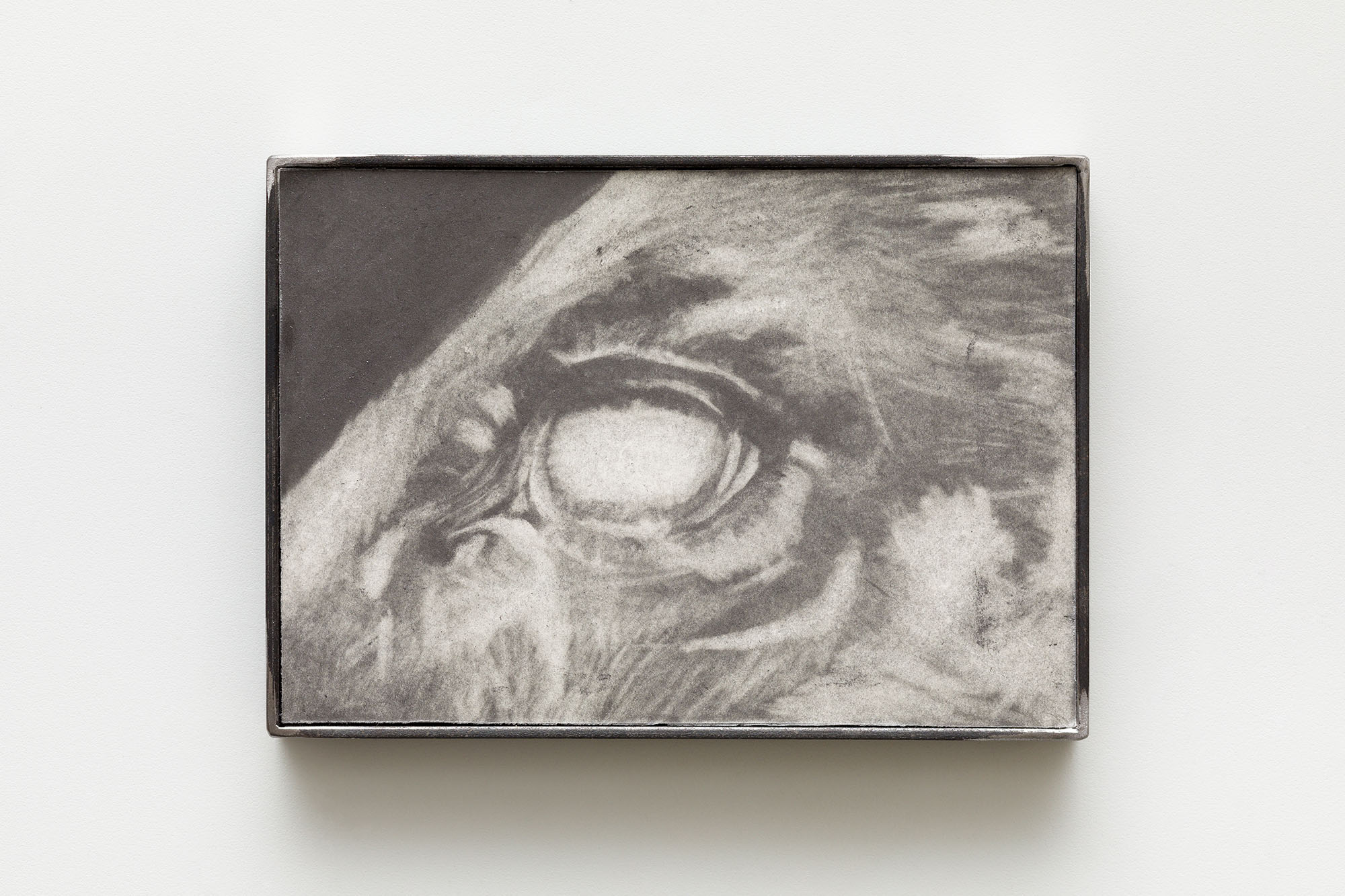

Silvio de Camillis Borges’ works consist on graphite drawings on paper, where the artist represents animals that flirt with ideas of bestiality, haziness and mystery. Interested in the accumulative process of the construction of images and the penetrability of this foggy and haunting figures on the subconscious, Borges dips an eraser in graphite powder and uses it as some kind of a brush. While it draws, the artist also erases some other areas of the process, reiterating the concern about the survival of imagetic symptoms and how memory operates in an ambiguous way. On steel frames with weld marks, Borges presents individual drawings of creatures such as a harpy, a pigeon, a blind horse, a bat, a queen conch, a piranha and a pirarucu, relating to the bestial and animal images that Vidor operates in its coats of arms.

On the exhibition space, the invited artist Gilson Plano performed an installation named Dois campos (“Two fields”), where he projected two intersected ellipses on the full space of the gallery. The lines of the ellipses were dotted, and where each mark touched the wall, the artist drilled a hole and planted a seed of favela on the left ellipse or a lead sphere on the right one. He then sealed the holes with spackling paste, resembling a war wound quickly closed, the marks of stray bullets on the walls of the houses in favelas and the everlasting scars of violence on Brazilian flesh. With Dois campos, Plano proposes a reading of Brazilian territory as fully taken by two forces in attrition: resistance and violence.

The discussion about forces upon territory are also explored by Plano in Meridianos (“Meridians”), a sculpture made of leather, iron and needles. He lengthens a piece of leather supported by two iron rods, with dozens of trespassing needles creating a line that resembles a territory demarcation, but also can demonstrate how politics of territory can be structured upon the violation of black people.

With a critical essay by the curator Carollina Lauriano, Animal Ferido is exhibited at VERVE, São Paulo, until January 22, 2023.

Texto originalmente publicado na Terremoto, em 18 de janeiro de 2023

Looking from a distance, as in a hunting position, the gallery is surrounded by an earth-colored curtain. At first sight, it is not known whether it is an armor, as a protection of what is kept inside, or an adornment that confers power, like a royal mantle. Maybe inside dwells the animal ferido (“wounded animal”) that entitles the show. Maybe it still needs protection, at the same time it flaunts his comeback.

The Brazilian artist Igor Vidor (São Paulo, 1985) presents a new body of work that deepens his research on violence, crime, politics and instances of power in Brazil. The works can be critically read under the analogous image of the cuirass, or the thickened skin of a wounded animal that has strengthened by being continuously wounded. The argument showcases the duality of the lacerated skin: being a proof of vulnerability that simultaneously grants an element of protection. The artist presents big sculptures made of bulletproof fabric and iron representing allegories of power, sculptures about traffic of drugs and guns, and installations with earth and cloth. Some of the works present bullet shells collected on the streets of Rio de Janeiro in crossfire, reminding that every ammo casing found on the ground is the skin of a materialized attempt to tear down a body. Vidor’s works showcase how the skin can be shattered, trespassed by a bullet, but also be a camouflage, a disguise, a bulletproof vest—or a cuirass made by skinning oppressed people alive by brutal force and using it as a golden fleece.

Animal Ferido is the first solo show by the artist after his 3-year political exile in Germany. Between the two rounds of the Brazilian presidential election that would elect Jair Bolsonaro in 2018, Vidor emphasized through his works the death of marginalized youths and the relationship between drug trafficking, political figures and power structures in Rio de Janeiro. After several death threats to him and his family for his impactful work, opening wide the dynamics of ultraviolence between public security, government institutions and the militias, the artist managed to flee the country in 2019. Vidor was sheltered by the Martin Roth Initiative, a program promoted by Germany’s Institute of Exterior Relations and Goethe Institute, for political protection of artists at risk from all over the globe. After developing his artistic research on residency programs in Europe—as Künstlerhaus Bethanien, in Berlin, and Pro Helvetia South America, in Zurich—, the artist is reestablishing his connections with his homeland, in an optimistic moment of decay of the right-wing conservatism caused by the comeback election of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva for Presidency on the end of last October.

Through the exhibited works, Vidor tries to construct a genealogy of violence from the first related events since the establishment of a republic in Brazil, setting a historic mark since the War of Canudos from 1897—the deadliest civil war in Brazilian history. It happened a year after the abolition of slavery in the country, when an armed combat took place between military and civil forces in northeastern Brazil. Vidor illustrates this narrative with the image of a tree named favela, very common on Canudos, that gave name to a type of urban occupation—close to a ghetto or a slum—that occurs specifically in Brazil. Baptizing these takeover spaces with the name of this plant is a form of resistance and irradiation of defiance.

The curtain that circle the gallery—on the same tone as the soil from Canudos, as the walls are painted with the earth itself—is stamped with handmade drawings of the favela plant and guns used on the war, denouncing how Brazilian flora is merged with a technology expressed through the armamentist production. This relation between an exoticism linked to Brazilian nature—from colonial times, with the naturalist expeditions—and the bestiality that these visual codes confer to a discourse of violence in the country is operated by the artist in his sculptures from the series Alegoria do terror (“Allegory of terror”).

On bulletproof aramid—fabric of which the Brazilian market is one of the top consumers, used in armoring cars and making bulletproof vests—Vidor inserts images by ultraviolet printing, operating symbols that constitute hundreds of badges of military police and special operations researched by the artist. These emblems merge European traditions of heraldry—usually employed on coats of arms—and a certain savagery linked to the Brazilian fauna, consciously referring to tradition and fear. The artist then mixes this arsenal of images with distorted photos of Brazilian Supreme Court members, architectural elements of government buildings, fragments of historic paintings, Portuguese royal jewelry from the Brazilian colonial age, and Viagra pills—believe it or not, 35,000 of them were bought in 2022 by Brazilian Armed Forces with public money under Jair Bolsonaro’s presidency.

The fabric that presents the images is held by an iron structure, as a metaphor that all allegories of violence, meticulously thought out, have a dense warlike backstage behind them. Analogously, Vidor’s criticisms about the incisions made upon the oppressed skin can be read as a clash with Eurocentric artistic tradition that has its main medium as a canvas stretched on a frame, as a skin tensioned over a chassis. While colonialist technology is always appointed to exploitation dynamics, the artist turns the cycle inside out when using the bulletproof fabric made in Europe to support his denunciations to the rooted violence.

For the show, Vidor invited two fellow artists to exhibit their works amongst his: Silvio de Camillis Borges (São Paulo, 1985) and Gilson Plano (Goiânia, 1988). Vidor proposed a narrative that only finds true meaning in collaboration, in the dialogue between combatants of a collective struggle. In the world of contemporary galleries, where artists duel for solo shows and hoist individuality as an ensign, the possibility of collaboration and integration of unrepresented artists is utterly arduous.

Silvio de Camillis Borges’ works consist on graphite drawings on paper, where the artist represents animals that flirt with ideas of bestiality, haziness and mystery. Interested in the accumulative process of the construction of images and the penetrability of this foggy and haunting figures on the subconscious, Borges dips an eraser in graphite powder and uses it as some kind of a brush. While it draws, the artist also erases some other areas of the process, reiterating the concern about the survival of imagetic symptoms and how memory operates in an ambiguous way. On steel frames with weld marks, Borges presents individual drawings of creatures such as a harpy, a pigeon, a blind horse, a bat, a queen conch, a piranha and a pirarucu, relating to the bestial and animal images that Vidor operates in its coats of arms.

On the exhibition space, the invited artist Gilson Plano performed an installation named Dois campos (“Two fields”), where he projected two intersected ellipses on the full space of the gallery. The lines of the ellipses were dotted, and where each mark touched the wall, the artist drilled a hole and planted a seed of favela on the left ellipse or a lead sphere on the right one. He then sealed the holes with spackling paste, resembling a war wound quickly closed, the marks of stray bullets on the walls of the houses in favelas and the everlasting scars of violence on Brazilian flesh. With Dois campos, Plano proposes a reading of Brazilian territory as fully taken by two forces in attrition: resistance and violence.

The discussion about forces upon territory are also explored by Plano in Meridianos (“Meridians”), a sculpture made of leather, iron and needles. He lengthens a piece of leather supported by two iron rods, with dozens of trespassing needles creating a line that resembles a territory demarcation, but also can demonstrate how politics of territory can be structured upon the violation of black people.

With a critical essay by the curator Carollina Lauriano, Animal Ferido is exhibited at VERVE, São Paulo, until January 22, 2023.

Texto originalmente publicado na Terremoto, em 18 de janeiro de 2023

Igor Vidor, Sem título (cortina), 2022.

Igor Vidor, Animal Ferido, vista da exposição, 2022.

Igor Vidor, Cópula cloaca, 2022.

Igor Vidor, Animal Ferido, vistas da exposição, 2022.

Gilson Plano, Meridianos, 2019.

Silvio de Camillis Borges, Sem título (cavalo cego), 2022.

Igor Vidor, A Vingança, 2022.