2021. Ocean Vuong

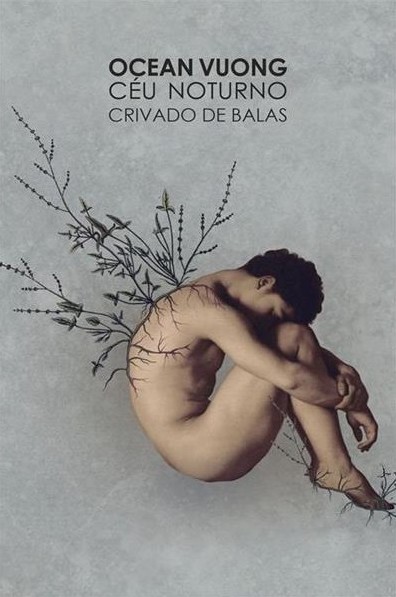

Night Sky with Exit Wounds is a book of poems by the Vietnamese author Ocean Vuong, born in 1988. As a young author, he’s already experienced literary recognition, being published in several countries, translated in multiple languages, having won awards (as the T.S. Eliot poetry award in 2017) and captivated a faithful crowd of readers. The beautiful book approaches some very dense and complex questions, such as Vietnamese diaspora, Saigon’s fall and the period when Vuong lived on a refugee field in the Philippines in early life. His arrival with his family in the United States of America, the country where he lives now, was extremely troublesome.

According to Galindo (2019, p. 12-13), Vuong’s first named wasn’t “Ocean'' when he went to the US, but her mother thought it was beautiful to rebaptize her son with the name of something that could link two very distant countries, such as the US and Vietnam - because the boy himself made this connection. His sensibility on being a foreigner, being part of the LGBTQIA+ community and coming from a penniless family running away from an unstable political situation in their home country is completely striking, making his work so powerful, contemporary and touching. It feels like closing your eyes, breathing deeply and enjoying the breeze that caresses your face - although, in fact, it's not a breeze: it’s a city-wrecking tornado.

Sometimes it seems to me that Vuong is almost an encounter between Charles Bukowski (1920-1994) and Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986). The narrated author’s hallucination is no longer caused by excessive drugs and abusive lifestyle with lack of health, but seems to be influenced by a series of events, like complex post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), that is so present in our contemporaneity. These hallucinations, however, aren’t on the junkie-Bukowski vibe, but place themselves on the glittering fogginess of Borges’ dreams. It makes you contemplate the beauty behind madness. The poems are like a dream-tale written by Borges, although it is also structured on roughness, so present in Bukowski's literature. In the Vuong’s fields of the Lord, you don’t see unicorns, as Borges would place them, but beautiful, dead and dark horses like J. K. Rowling’s thestrals [1].

Although Vuong brings out some very particular events – like the painful Vietnamese diaspora caused by the war, his relationship with his suffered (and almost ghostly) parents, the internal mishaps and struggles on his sexual orientation – and how they shaped his persona (in the most cringe and glorious ways), he writes in a way that makes a compulsory autopsy on the soul of the one who reads. He can make you feel, through his inner and particular landmarks, the pain that you felt when you lived the same things, although through completely different events. This textual relation between difference and repetition, of how life can be beautiful through pain, even though each and every person has a different experience of it, makes Vuong’s PTSD-writing so present, so contemporary [2], so solid. His texts brings out a sensation of familiarization and identification by weirdness: they make you feel like you’re not the only teenager or young adult thinking about crazy things: I think Sally Rooney’s Normal People (2018) and Rupi Kaur’s milk and honey (2015) paved some of the literary road that Vuong explores so brightly.

His writing is surely not light. And by “not light”, I don’t mean it’s dark, just that it’s heavy: it’s a very dense atmosphere, like a milky and foggy air – but it almost showcases a window to heaven. It is as if the smell of the roses that are placed upon the ethereal tombstone of your living mother turns into the only atmosphere possible. You doubt if everything you see is a dream, because no one could narrate it if not yourself, but you surely feel like it is the most beautiful nightmare you can ever have. Vuong safely traverses through the fields of the sublime and Dionysian beauty. It gets even more complex when Vuong masters textual form, playing with metrics, sizes, diagramation, alignments, phrase-breaks and the material and visual aspects of the text. Sometimes it seems like a haikai, a Walt Whitman’s poem, a Joycean thunder [3] or a strictly metric Alexandrine verse.

He balances between the scatology of contemporary-personal traumas and the sublime beauty of seeing ghosts as angels. It’s as if gunshots are the heaven trumpets. It’s as if a glazing look of a loved one is the explosion of a grenade [4]. It’s the beauty, the vulnerability of love (and of the self) and the fear of trust, as in Rest Energy performance [5]. Drowning in dark waters seems like a peaceful meditation; sinking is like finding its place. Voung’s perspective on beauty through ugliness (or on the “conventional standard of beauty”, better saying) and the other way around is powerful because of its intense dynamic, like an ongoing and everlasting paradox: “A mother’s love / neglects pride / the way fire / neglects the cries / of what it burns” [6] (VUONG, 2019, p. 62).

[1] A thestral is a magical animal created by J. K. Rowling (b. 1965) on the Harry Potter series. It’s an imponent dark winged horse with a skeletal body, ghostly face with reptilian features and very wide bat-wings. They’re only visible to those who have witnessed death. They hold a very particular aesthetics, that merge elegance and darkness. (ROWLING, 2003, p. 196-199).

[2] Vuong’s work is shown on the HBO’s TV series We Are Who We Are (2020), by the Italian director Luca Guadagnino (b. 1971), where one of the main characters (Fraser) reads Night Sky with Exit Wounds and talks about the forthcoming novel of the author, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, with the man he’s in love with (Jonathan).

[3] About the Joycean thunder, I emphasize: FECHBACH, 1991.

[4] On “Notebook fragments'', a poem on Night Sky with Exit Wounds, Voung refers to grenades a couple of times: “In Vietnamese, the word for grenade is ‘bom’, from the French ‘pomme’, / meaning ‘apple’. / Or was it American for ‘bomb’?” (p. 168); and “Some grenades explode with a vision of white flowers (p. 172).

[5] Rest Energy is a performance enacted by Marina Abramović (b. 1946) and Ulay (1943-2020) in Amsterdam, in 1980. The performance is based on Ulay holding an armed bow, with Abramović holding the point of the arrow pointed to her heart. Her body is hanging back and the only support is the bow and arrow pointing to her heart. It’s a performance about trust, about love, about trusting your life in the hands of a loved one (and on the unforeseen possibilities. Two microphones were placed near their hearts, so the heartbeats could be listened to.

[6] This is a fragment of a poem called “Headfirst”, on Night Sky With Exit Wounds.

DELEUZE, Gilles. Différence et répetition. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1993.

FECHBACH, Sidney. “The Hundredlettered Name: Thunder in James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake”. New Queries in Aesthetics and Metaphysics. Analecta Husserliana (The Yearbook of Phenomenological Research), vol 37. Springer, Dordrecht, 1991, p. 283-297.

GALINDO, Rogerio W. “Belo e original”. In: VUONG, Ocean. Night Sky with Exit Wounds / Céu noturno crivado de balas. 1st edition, Bilingual, with the original text in English and translation to Portuguese by Rogerio W. Galindo. Belo Horizonte: Editora Âyiné, 2019, p. 11-15.

KAUR, Rupi. milk and honey. Kansas City: Andrews McMeel Publishing, 2015.

ROONEY, Sally. Normal People. London: Faber and Faber, 2018.

VUONG, Ocean. On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous. New York: Penguin Press, 2019.

VUONG, Ocean. Night Sky with Exit Wounds / Céu noturno crivado de balas. 1st edition, Bilingual, with the original text in English and translation to Portuguese by Rogerio W. Galindo. Belo Horizonte: Editora Âyiné, 2019.

ROWLING, J. K. Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix. London: Arthur A. Levine Books/Scholastic Press, 2003.

Texto originalmente publicado na revista Asas da Palavra (UNAMA), v. 18, n. 2, em dezembro de 2021.

According to Galindo (2019, p. 12-13), Vuong’s first named wasn’t “Ocean'' when he went to the US, but her mother thought it was beautiful to rebaptize her son with the name of something that could link two very distant countries, such as the US and Vietnam - because the boy himself made this connection. His sensibility on being a foreigner, being part of the LGBTQIA+ community and coming from a penniless family running away from an unstable political situation in their home country is completely striking, making his work so powerful, contemporary and touching. It feels like closing your eyes, breathing deeply and enjoying the breeze that caresses your face - although, in fact, it's not a breeze: it’s a city-wrecking tornado.

Sometimes it seems to me that Vuong is almost an encounter between Charles Bukowski (1920-1994) and Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986). The narrated author’s hallucination is no longer caused by excessive drugs and abusive lifestyle with lack of health, but seems to be influenced by a series of events, like complex post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), that is so present in our contemporaneity. These hallucinations, however, aren’t on the junkie-Bukowski vibe, but place themselves on the glittering fogginess of Borges’ dreams. It makes you contemplate the beauty behind madness. The poems are like a dream-tale written by Borges, although it is also structured on roughness, so present in Bukowski's literature. In the Vuong’s fields of the Lord, you don’t see unicorns, as Borges would place them, but beautiful, dead and dark horses like J. K. Rowling’s thestrals [1].

Although Vuong brings out some very particular events – like the painful Vietnamese diaspora caused by the war, his relationship with his suffered (and almost ghostly) parents, the internal mishaps and struggles on his sexual orientation – and how they shaped his persona (in the most cringe and glorious ways), he writes in a way that makes a compulsory autopsy on the soul of the one who reads. He can make you feel, through his inner and particular landmarks, the pain that you felt when you lived the same things, although through completely different events. This textual relation between difference and repetition, of how life can be beautiful through pain, even though each and every person has a different experience of it, makes Vuong’s PTSD-writing so present, so contemporary [2], so solid. His texts brings out a sensation of familiarization and identification by weirdness: they make you feel like you’re not the only teenager or young adult thinking about crazy things: I think Sally Rooney’s Normal People (2018) and Rupi Kaur’s milk and honey (2015) paved some of the literary road that Vuong explores so brightly.

His writing is surely not light. And by “not light”, I don’t mean it’s dark, just that it’s heavy: it’s a very dense atmosphere, like a milky and foggy air – but it almost showcases a window to heaven. It is as if the smell of the roses that are placed upon the ethereal tombstone of your living mother turns into the only atmosphere possible. You doubt if everything you see is a dream, because no one could narrate it if not yourself, but you surely feel like it is the most beautiful nightmare you can ever have. Vuong safely traverses through the fields of the sublime and Dionysian beauty. It gets even more complex when Vuong masters textual form, playing with metrics, sizes, diagramation, alignments, phrase-breaks and the material and visual aspects of the text. Sometimes it seems like a haikai, a Walt Whitman’s poem, a Joycean thunder [3] or a strictly metric Alexandrine verse.

He balances between the scatology of contemporary-personal traumas and the sublime beauty of seeing ghosts as angels. It’s as if gunshots are the heaven trumpets. It’s as if a glazing look of a loved one is the explosion of a grenade [4]. It’s the beauty, the vulnerability of love (and of the self) and the fear of trust, as in Rest Energy performance [5]. Drowning in dark waters seems like a peaceful meditation; sinking is like finding its place. Voung’s perspective on beauty through ugliness (or on the “conventional standard of beauty”, better saying) and the other way around is powerful because of its intense dynamic, like an ongoing and everlasting paradox: “A mother’s love / neglects pride / the way fire / neglects the cries / of what it burns” [6] (VUONG, 2019, p. 62).

[1] A thestral is a magical animal created by J. K. Rowling (b. 1965) on the Harry Potter series. It’s an imponent dark winged horse with a skeletal body, ghostly face with reptilian features and very wide bat-wings. They’re only visible to those who have witnessed death. They hold a very particular aesthetics, that merge elegance and darkness. (ROWLING, 2003, p. 196-199).

[2] Vuong’s work is shown on the HBO’s TV series We Are Who We Are (2020), by the Italian director Luca Guadagnino (b. 1971), where one of the main characters (Fraser) reads Night Sky with Exit Wounds and talks about the forthcoming novel of the author, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, with the man he’s in love with (Jonathan).

[3] About the Joycean thunder, I emphasize: FECHBACH, 1991.

[4] On “Notebook fragments'', a poem on Night Sky with Exit Wounds, Voung refers to grenades a couple of times: “In Vietnamese, the word for grenade is ‘bom’, from the French ‘pomme’, / meaning ‘apple’. / Or was it American for ‘bomb’?” (p. 168); and “Some grenades explode with a vision of white flowers (p. 172).

[5] Rest Energy is a performance enacted by Marina Abramović (b. 1946) and Ulay (1943-2020) in Amsterdam, in 1980. The performance is based on Ulay holding an armed bow, with Abramović holding the point of the arrow pointed to her heart. Her body is hanging back and the only support is the bow and arrow pointing to her heart. It’s a performance about trust, about love, about trusting your life in the hands of a loved one (and on the unforeseen possibilities. Two microphones were placed near their hearts, so the heartbeats could be listened to.

[6] This is a fragment of a poem called “Headfirst”, on Night Sky With Exit Wounds.

DELEUZE, Gilles. Différence et répetition. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1993.

FECHBACH, Sidney. “The Hundredlettered Name: Thunder in James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake”. New Queries in Aesthetics and Metaphysics. Analecta Husserliana (The Yearbook of Phenomenological Research), vol 37. Springer, Dordrecht, 1991, p. 283-297.

GALINDO, Rogerio W. “Belo e original”. In: VUONG, Ocean. Night Sky with Exit Wounds / Céu noturno crivado de balas. 1st edition, Bilingual, with the original text in English and translation to Portuguese by Rogerio W. Galindo. Belo Horizonte: Editora Âyiné, 2019, p. 11-15.

KAUR, Rupi. milk and honey. Kansas City: Andrews McMeel Publishing, 2015.

ROONEY, Sally. Normal People. London: Faber and Faber, 2018.

VUONG, Ocean. On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous. New York: Penguin Press, 2019.

VUONG, Ocean. Night Sky with Exit Wounds / Céu noturno crivado de balas. 1st edition, Bilingual, with the original text in English and translation to Portuguese by Rogerio W. Galindo. Belo Horizonte: Editora Âyiné, 2019.

ROWLING, J. K. Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix. London: Arthur A. Levine Books/Scholastic Press, 2003.

Texto originalmente publicado na revista Asas da Palavra (UNAMA), v. 18, n. 2, em dezembro de 2021.

VUONG, Ocean. Céu noturno crivado de balas/Night sky with exit wounds [Edição bilíngue]. Belo Horizonte: Editora Âyiné, 2019.

VUONG, Ocean. Céu noturno crivado de balas/Night sky with exit wounds [Edição bilíngue]. Belo Horizonte: Editora Âyiné, 2019.Compre