Paula Siebra, As primeiras coisas, Mendes Wood DM, New York, 2024.

2024. Paula Siebra

As primeiras coisas

Texto crítico da exposição individual da artista na galeria Mendes Wood DM, em Nova York

WEB

Texto crítico da exposição individual da artista na galeria Mendes Wood DM, em Nova York

WEB

10.10-09.11.2024

Mendes Wood DM, Nova York

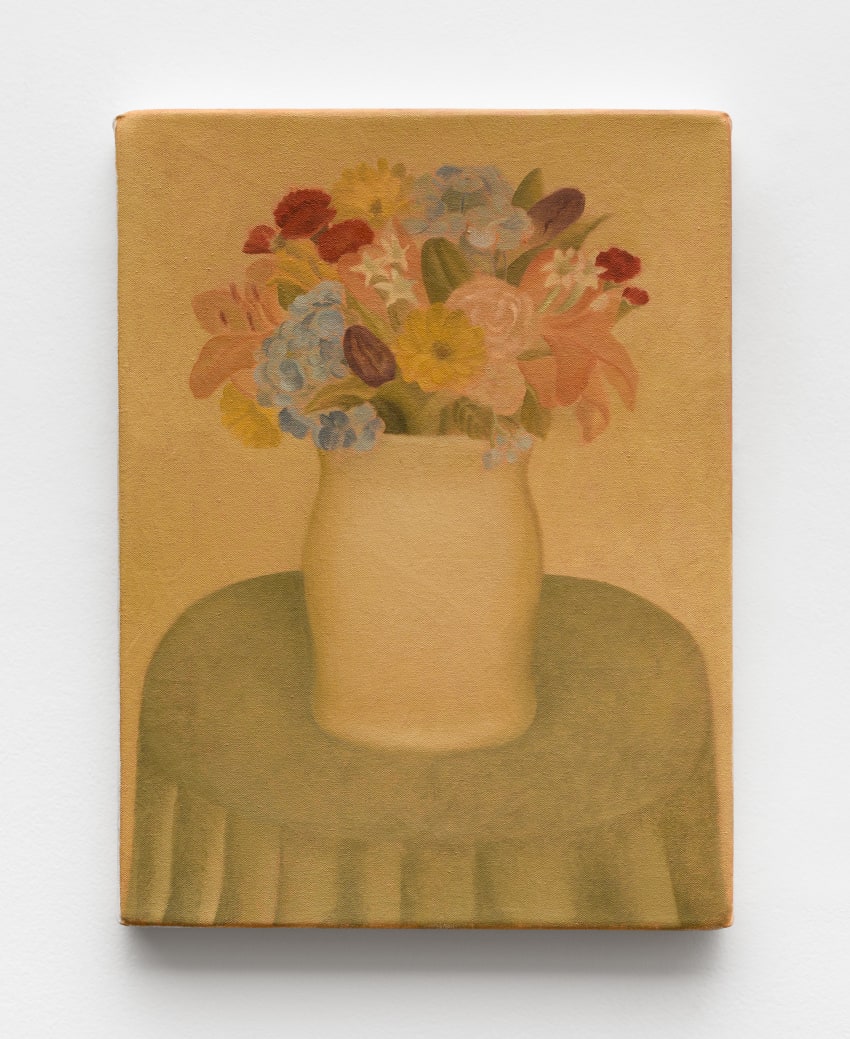

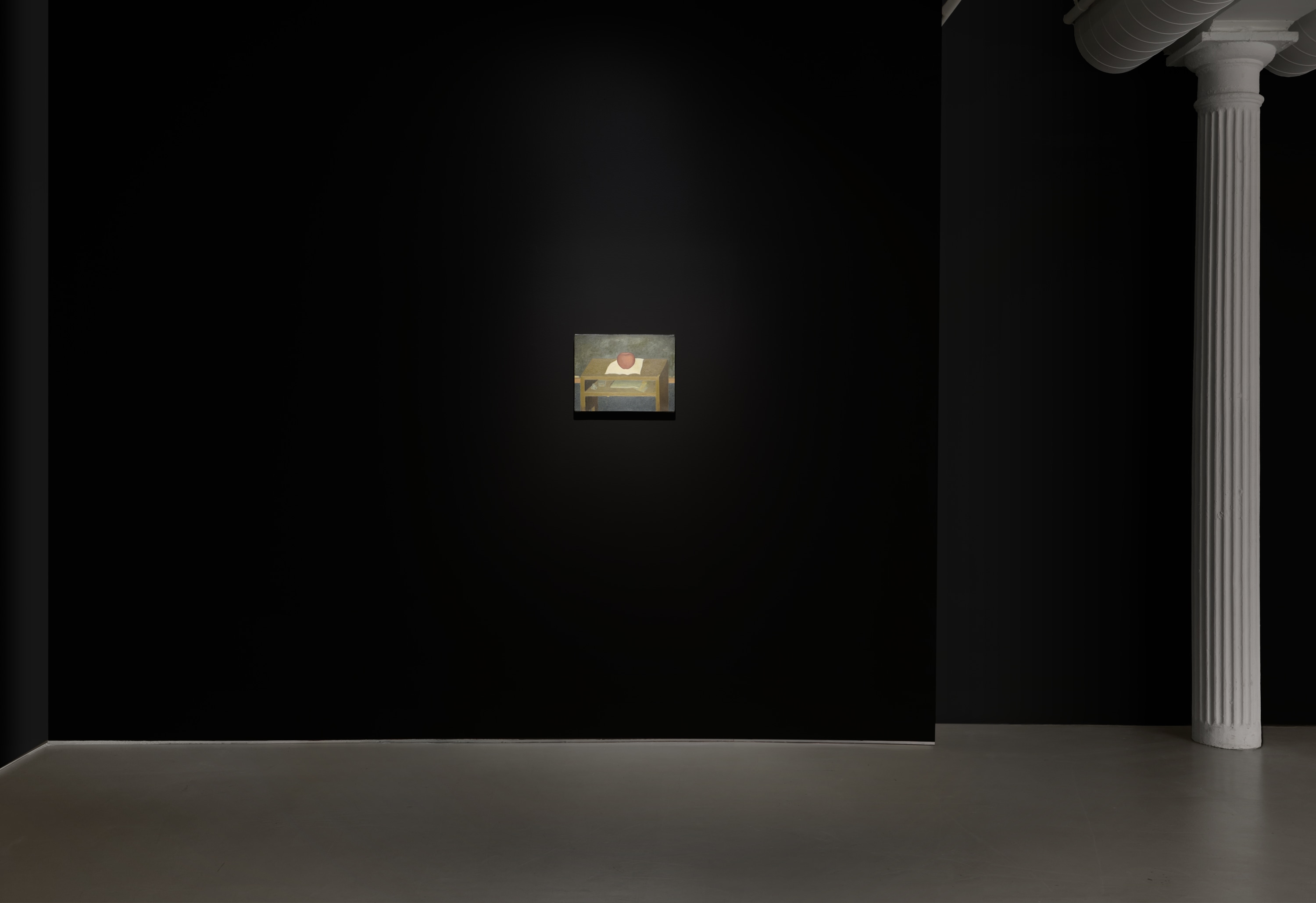

Mendes Wood DM presents As primeiras coisas [The earliest things], a painting exhibition by Paula Siebra. Siebra carves out primordial imagery from ubiquitous objects, signs, and emotions that invite the observer to immerse themselves in memorial contexts and lyrical reverberations. From an initial laconicism — reflected in the conciseness of the titles and the seeming synthesis of elements in the paintings — and with a devastating directness, each image is incisively delivered like dense crystals that may take ages to dissolve, memories in their quintessential stage. Siebra’s paintings reflect on collective memories, social relations, subjectivities, and human desires, embalmed by a metaphysical and nostalgic atmosphere.

Identifying the most primordial things in image and life, Siebra draws a cartography of returns: painting the places she has visited, whether through circumstance or memory, and anchors herself while facing the unceremonious accumulation of life’s abrupt movements. The freshly laundered clothes that return to the bed, the pens that neatly revisit the shirt pocket, the imprisoned feelings that are sealed in an envelope and freed into the world. Although allegorically presented in isolated scenes, the paintings engender an interconnected macrocosm through affective and semiological mechanisms. Similarly, while the works bear the inescapable personal perception of the artist, they are reflected in the desired postulation of a collective representational will, where the universal and the particular amalgamate.

Siebra’s remarkable semantic assertiveness is not limited to formal representation; it extends to capturing the poetic essence of the subject’s encounters with these objects, which, in a sense, also transform into subjects themselves. In their daily repetition, these intimate living objects prove valuable by remaining constant and emphasized over a dilated time arc. Although some inevitably have their origins linked to a factory seriality, Siebra proposes an individualization of objects that radiate their subjectivities because they belong to someone special, holding non-transferable stories and bearing witness to a life thirsty for yeses. (“All the world began with a yes. One molecule said yes to another molecule and life was born. But before prehistory there was the prehistory of prehistory and there was the never and there was the yes.”[1] )

This undeniable, raw, and bare realism in Siebra’s work fuels an inexhaustible imaginative power, continuously attracting layers of meaning and depth to her poetic expression. Furthermore, it is crucial to remember that an object’s idealization and narrative fabulation do not annul its underlying reality. In O Piano, Siebra’s archetypal search is so impetuous that it produces an instrument with one hundred keys, perhaps more absolute and memorable than the usual one with eighty-eight. The surplus dozen stands as a firm and deep voice that attests to the truth of the picture. The octaves are extended and the images of fascination are prolonged, just like the wavy golden hair that spreads beyond the limits of the double bed in Cochilo, drawing a dreamlike topology close to Dunas.

In this reservoir of substance — and in whatever order this essence is constituted —, Siebra lists and produces these scenes driven by a feeling of zeal: not only in physical care, such as in the meticulous organization of the suitcase and the polishing of the low-heeled shoes, but in the esteem of indelible memories. It is as if the artist is constantly collecting something in the midst of a lost and careless world, “promising it a life of warmth and security.” [2] This heed is conveyed in investigating the best position and light that a given object can have in a composition, a ballast provided by the painter’s extreme erudition in the history of painting and the tradition of still life. Moreover, Siebra ties personal connections while revisiting her favorite painters, as if carefully organizing a toolbox of affectivities: the primordial image and the force of the almost banal life of Antonio Donghi, the mnemonic centrality of Domenico Gnoli, the subtle tones and cooked light of Albert York, the careful placement and spatial coexistence of Giorgio Morandi.

In disagreement with what an obsolete image theory defended – that a given artist was passively influenced by other preceding artists –, Siebra attests to an active influence: she “makes an intentional selection from an array of resources in the history of her craft” [3]. This active action also opposes the artificial power of art history and of crafting an organization of things, making her painting proudly manifest traces of the experience of the place where she was born, Fortaleza, Brazil, but which expands through a profound erudition to constellational visualities, merging very different geographical and historical contexts. In this tone, Siebra impregnates fiction with so much reality and the lived experience with so much fable that this threshold fades and is rebuilt, like shifting sand castles.

With ambiguous inexhaustibility and iconological possibilities, the painter presents particular objects drenched in poetic suggestion. An apple, for instance: the care taken in polishing the skin wrapped in a handkerchief, its presence in the fruit bowl on the set table, the grateful pride placed on the teacher’s desk, its erotic silhouette, the synthesis of original sin, the first desire. There is, therefore, no attempt to establish a Platonic idea of things but rather an endeavor to access the very core of the painter’s imagination. These crystalline images, pure to the same extent that they are fragile, show Siebra’s intertwining of psychoanalysis and the construction of imagetic archetypes that flirt with their unconscious potencies.

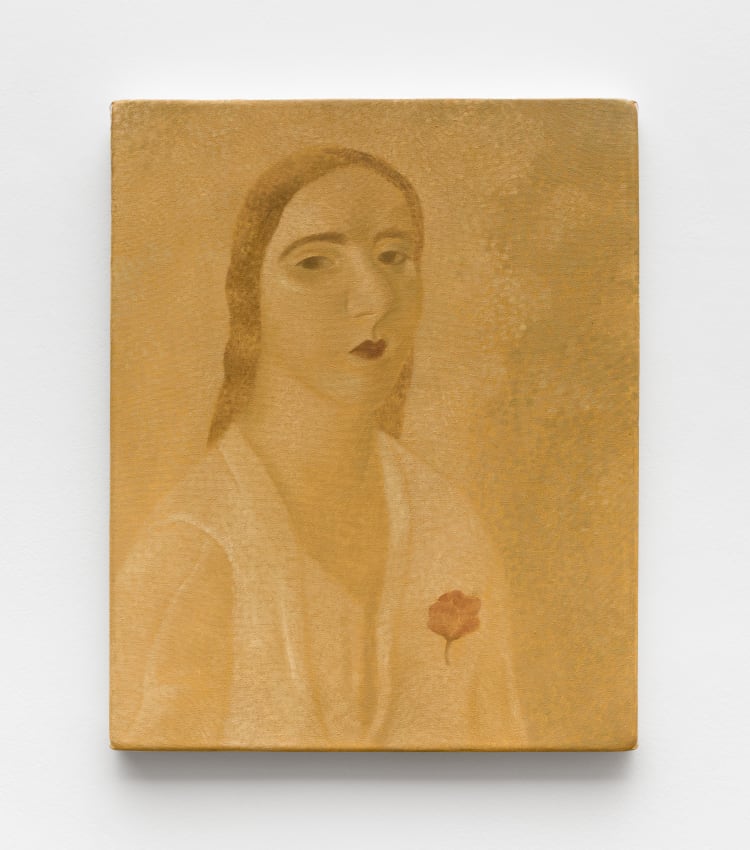

Siebra’s paintings recall the arduous and brave exercise of recalling distant memories embedded in the unconscious: one imagines remembering with such force, with eyes closed and pressed tightly, holding the breath, as if giving birth to an image that comes into the world in sparks through one’s ears. Her images are subtly manifested in their unmediated renditions. Sitting at the table carefully set only for herself, opening a sketchbook to work, and placing a flower in her lapel announces a daily determination to face the world, the strength to deal with life’s overwhelming beauty and pain in an unassuming act as if to say: “World, I am here to suffer for you. To die of love for every single thing. I am here, lone, ready. It is on me.”

Notes

[1] Clarice Lispector, The hour of the star. New York: New Directions Books, 2011 (originally published in Portuguese in 1977), translated by Ben Moser, p. 14.

[2] Virginia Woolf, “Solid objects” (1920) in Virginia Woolf, A Haunted House: The Complete Shorter Fiction (ed. Susan Dick). London: Vintage, 2003, p. 98.

[3] Michael Baxandall, Patterns of intention: on the historical explanation of pictures. New Haven/London: Yale University Press, 1985, p. 59. The original quote ends with “his craft,” here changed to “her craft” to meet Siebra’s practice.

Texto originalmente publicado na exposição “Na Boca do Sol” na galeria Mendes Wood DM, em Nova York, de 27 de janeiro a 2 de março de 2024

Mendes Wood DM, Nova York

Mendes Wood DM presents As primeiras coisas [The earliest things], a painting exhibition by Paula Siebra. Siebra carves out primordial imagery from ubiquitous objects, signs, and emotions that invite the observer to immerse themselves in memorial contexts and lyrical reverberations. From an initial laconicism — reflected in the conciseness of the titles and the seeming synthesis of elements in the paintings — and with a devastating directness, each image is incisively delivered like dense crystals that may take ages to dissolve, memories in their quintessential stage. Siebra’s paintings reflect on collective memories, social relations, subjectivities, and human desires, embalmed by a metaphysical and nostalgic atmosphere.

Identifying the most primordial things in image and life, Siebra draws a cartography of returns: painting the places she has visited, whether through circumstance or memory, and anchors herself while facing the unceremonious accumulation of life’s abrupt movements. The freshly laundered clothes that return to the bed, the pens that neatly revisit the shirt pocket, the imprisoned feelings that are sealed in an envelope and freed into the world. Although allegorically presented in isolated scenes, the paintings engender an interconnected macrocosm through affective and semiological mechanisms. Similarly, while the works bear the inescapable personal perception of the artist, they are reflected in the desired postulation of a collective representational will, where the universal and the particular amalgamate.

Siebra’s remarkable semantic assertiveness is not limited to formal representation; it extends to capturing the poetic essence of the subject’s encounters with these objects, which, in a sense, also transform into subjects themselves. In their daily repetition, these intimate living objects prove valuable by remaining constant and emphasized over a dilated time arc. Although some inevitably have their origins linked to a factory seriality, Siebra proposes an individualization of objects that radiate their subjectivities because they belong to someone special, holding non-transferable stories and bearing witness to a life thirsty for yeses. (“All the world began with a yes. One molecule said yes to another molecule and life was born. But before prehistory there was the prehistory of prehistory and there was the never and there was the yes.”[1] )

This undeniable, raw, and bare realism in Siebra’s work fuels an inexhaustible imaginative power, continuously attracting layers of meaning and depth to her poetic expression. Furthermore, it is crucial to remember that an object’s idealization and narrative fabulation do not annul its underlying reality. In O Piano, Siebra’s archetypal search is so impetuous that it produces an instrument with one hundred keys, perhaps more absolute and memorable than the usual one with eighty-eight. The surplus dozen stands as a firm and deep voice that attests to the truth of the picture. The octaves are extended and the images of fascination are prolonged, just like the wavy golden hair that spreads beyond the limits of the double bed in Cochilo, drawing a dreamlike topology close to Dunas.

In this reservoir of substance — and in whatever order this essence is constituted —, Siebra lists and produces these scenes driven by a feeling of zeal: not only in physical care, such as in the meticulous organization of the suitcase and the polishing of the low-heeled shoes, but in the esteem of indelible memories. It is as if the artist is constantly collecting something in the midst of a lost and careless world, “promising it a life of warmth and security.” [2] This heed is conveyed in investigating the best position and light that a given object can have in a composition, a ballast provided by the painter’s extreme erudition in the history of painting and the tradition of still life. Moreover, Siebra ties personal connections while revisiting her favorite painters, as if carefully organizing a toolbox of affectivities: the primordial image and the force of the almost banal life of Antonio Donghi, the mnemonic centrality of Domenico Gnoli, the subtle tones and cooked light of Albert York, the careful placement and spatial coexistence of Giorgio Morandi.

In disagreement with what an obsolete image theory defended – that a given artist was passively influenced by other preceding artists –, Siebra attests to an active influence: she “makes an intentional selection from an array of resources in the history of her craft” [3]. This active action also opposes the artificial power of art history and of crafting an organization of things, making her painting proudly manifest traces of the experience of the place where she was born, Fortaleza, Brazil, but which expands through a profound erudition to constellational visualities, merging very different geographical and historical contexts. In this tone, Siebra impregnates fiction with so much reality and the lived experience with so much fable that this threshold fades and is rebuilt, like shifting sand castles.

With ambiguous inexhaustibility and iconological possibilities, the painter presents particular objects drenched in poetic suggestion. An apple, for instance: the care taken in polishing the skin wrapped in a handkerchief, its presence in the fruit bowl on the set table, the grateful pride placed on the teacher’s desk, its erotic silhouette, the synthesis of original sin, the first desire. There is, therefore, no attempt to establish a Platonic idea of things but rather an endeavor to access the very core of the painter’s imagination. These crystalline images, pure to the same extent that they are fragile, show Siebra’s intertwining of psychoanalysis and the construction of imagetic archetypes that flirt with their unconscious potencies.

Siebra’s paintings recall the arduous and brave exercise of recalling distant memories embedded in the unconscious: one imagines remembering with such force, with eyes closed and pressed tightly, holding the breath, as if giving birth to an image that comes into the world in sparks through one’s ears. Her images are subtly manifested in their unmediated renditions. Sitting at the table carefully set only for herself, opening a sketchbook to work, and placing a flower in her lapel announces a daily determination to face the world, the strength to deal with life’s overwhelming beauty and pain in an unassuming act as if to say: “World, I am here to suffer for you. To die of love for every single thing. I am here, lone, ready. It is on me.”

Notes

[1] Clarice Lispector, The hour of the star. New York: New Directions Books, 2011 (originally published in Portuguese in 1977), translated by Ben Moser, p. 14.

[2] Virginia Woolf, “Solid objects” (1920) in Virginia Woolf, A Haunted House: The Complete Shorter Fiction (ed. Susan Dick). London: Vintage, 2003, p. 98.

[3] Michael Baxandall, Patterns of intention: on the historical explanation of pictures. New Haven/London: Yale University Press, 1985, p. 59. The original quote ends with “his craft,” here changed to “her craft” to meet Siebra’s practice.

Texto originalmente publicado na exposição “Na Boca do Sol” na galeria Mendes Wood DM, em Nova York, de 27 de janeiro a 2 de março de 2024