Thiago Hattnher, Timing notes, vistas da exposição, 2024.

2024. Thiago Hattnher

Timing notes

Texto crítico da exposição individual do artista na galeria Jeremy Scholar, em Londres

WEB

Texto crítico da exposição individual do artista na galeria Jeremy Scholar, em Londres

WEB

01.06-30.08.2024 [cur. Brandy Cartens]

Jeremy Scholar, Londres

Note-taking is central to the keen observer’s behavior: briefly writing or drawing after perceiving something beautiful, despite most noteworthy things being ineffable. A labor of attempting to preserve an open memory, the note—in its polysemic play, from a musical indication to an annotated thought—holds a freedom of not comprising complete narratives, offering no rigorous context but rather alluring annotations for tale co-creation. At the same time, it proposes an empathetic sense of sharing personal impressions of the outer world generously and honestly, reaffirming one’s subjectivity while inviting the observer to experience a point of view and a state of mind. In Timing notes, Thiago Hattnher (b. 1990, São Paulo, Brazil) empathetically presents an autobiographical constellation of pictorial notes that carry a sense of timelessness, alive in the fleshiness of outdated memories and the evocative potency of lasting longings.

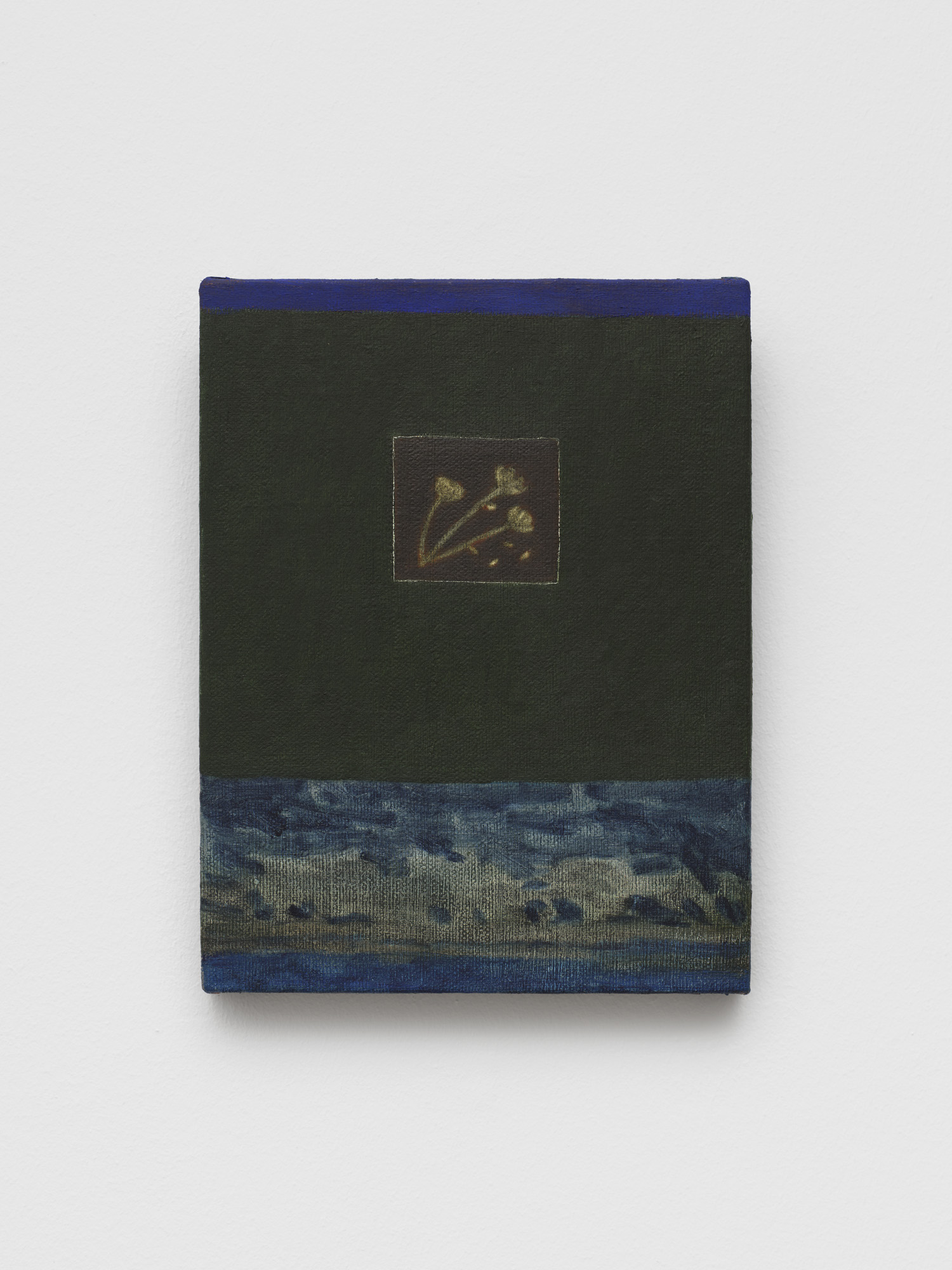

This pendulum dynamic between hopeful intent and candid decay—but also between how painting and music similarly deal with time—can synthesize Hattnher's ability to lock fleeting and ambiguous elements into concise, small-scale paintings. Congregating delicate chromatic and formal choices and extreme attention to the medium—which varies from rough burlap, collected wood, fine linen, and cotton canvases—, his works are recollections of images and experiences unrestricted by a rigid disciplinary genre. The moonlit, silvery quality of petals coexist with mirage-like landscapes, fogged, remembered, in hued geometric fields. Even through a severe accumulation process, the artist paints just enough to leave room for the untouched.

As non-linear diagrams, Hattnher’s paintings usually comprise color blocks, flower arrangements, and landscapes devised into a seemingly intuitive geometrical structure. Slight but sudden contrasting elements act as compositive and chromatic outbursts always directed towards a rhythmic intention, full of heterogeneous vibrations and tones, from lullabies to dramatic sonatas. Put in the same hierarchy—a blue rectangle is not a background, just as a flower bouquet or the silhouette of a hill do not obey the historical superiority attributed to a figure—, they are all imagetic and poetic experiments on rhythm, interval, and duration. Akin to a concert chart, these elements are multilayered, discoursing on these subjects not only in the relations between each other but within themselves: each part is a microcosm that reflects dense choices of paint handling, illumination by layer construction, hiatus between paint coats, and the ominous moment to stop and consider it finished. When assembled, they are finely orchestrated like the woodwinds, brass, percussion, strings, and keyboards of a symphony, each fulfilling a specific role individually and as a whole.

Hattnher reiterates the ambivalence of dealing with the image while it is being made. The defiance and the ball, the pause and the action, the uncontrolled fate and the planned desire—“I don’t hear music when I write it. I write it in order to hear something I haven’t heard yet”, as stated by John Cage [1], deeply impactful in Hattnher’s practice. This open posture not only illustrates the nuanced dynamics of the creative process but places the painter, a figure of action, into a realm of stillness, while the image, usually seen as passive, takes center stage. The painting performs, even unmoving.

As in John Cage’s and Stephen Drury’s In a Landscape, music from 1948, the two artists bend a robust repertoire of erudite music into experimentation. The multisensorial and melancholy music do not reference a Western musical tradition in easily recognizable citations but in a deep comprehension—and subversion—of its structure. These experimentations are familiar to Hattnher, and the pairing of music and painting in the reading of his work—and also in Cage’s and Drury’s In a Landscape—is not by chance. The vivid aspects of the creative process analogous to the reoperation of erudite knowledge can be exemplified through Hattnher’s profound admiration of the works of Albert York and Giorgio Morandi, to name just a few—the juxtaposition of still life and landscape in York’s paintings, mainly the ones between 1982 and 1983; and dissolution of the dem that often prevents the merging of abstraction and figuration in Morandi’s work.

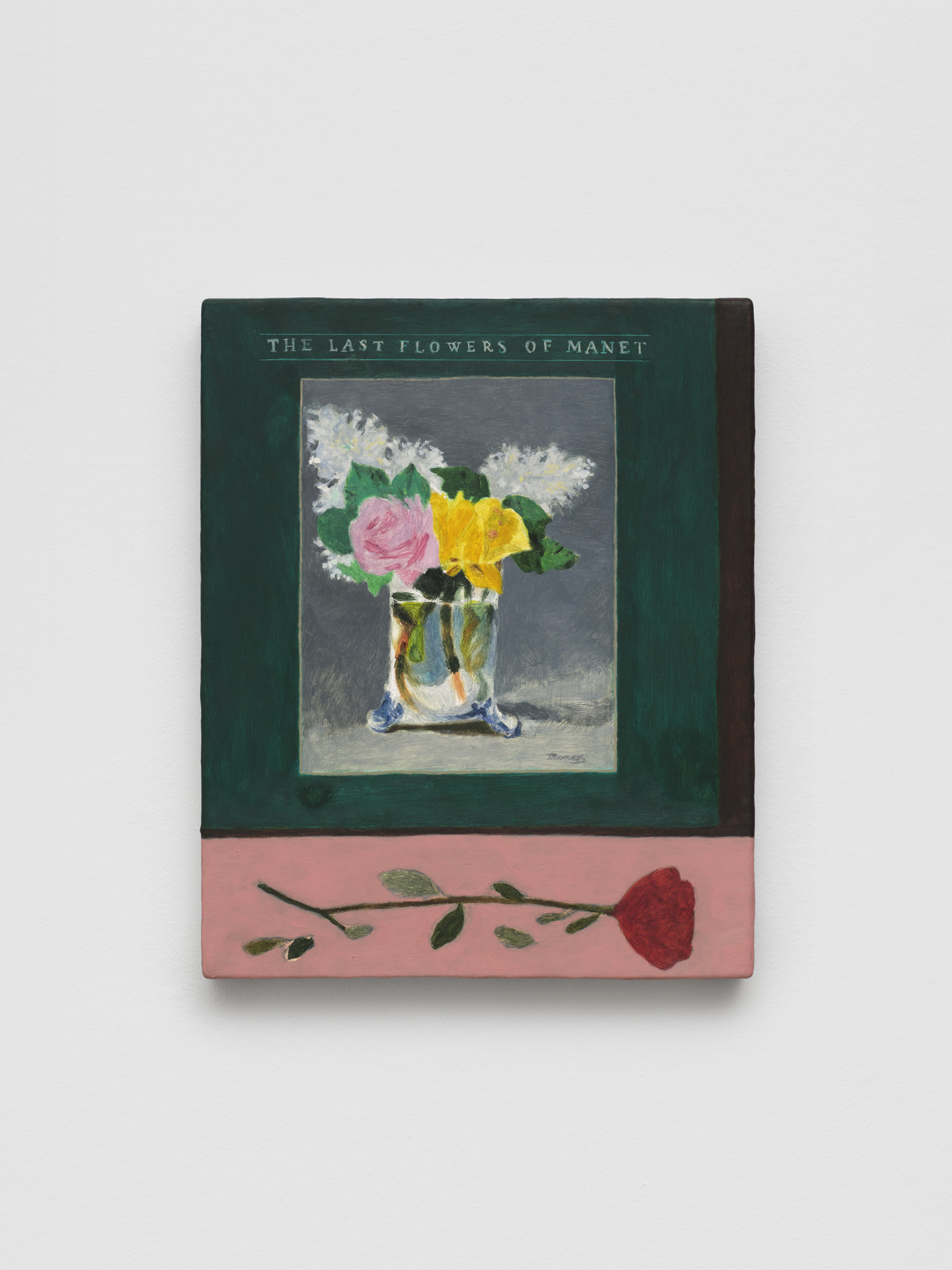

In timbre-enriching brushstrokes, Hattnher’s paintings balance the modesty of an attempt—as if proclaiming it is just a seemingly effortless attempt—and the dazzle of its assertive power, always rooted in profound erudition. The artist transmutes this ambiguity in the uneven rectangles, in the heterogeneity of the paint handling in the chromatic bodies, and in the active dialogue with grand themes of the history of painting—an exchange solidified through Hattnher’s awareness of the tradition of his craft. In this show, there is a direct reference to the last flowers painted by Édouard Manet through a 1988 dedicated book. By painting its cover—what Hattnher has previously done with publications on Louise Bourgeois, Pablo Picasso, Cy Twombly, and John Cage (again, as a chorus)—, he does not only refer to Manet’s painted flowers themselves but the endless reminiscences of memory that surround his relations with these paintings through and outside the book: the dark brown still-life atmosphere that was in the back of each flower vase; the decisiveness of some single brushstrokes that compose petals; the linen-and-gilded-wood frames that crowned most of the flower paintings but were left out in the book’s reproductions; the slightly faded, sunburnt book sleeve in emerald green; the analogic grainy aspect of the photographed painting elected to stamp its cover.

In another work, Hattnher paints a turquoise mosaic of white lilies under a vast, arid landscape scarred by a curved path. It resembles the image of the same lily but replicated as if seen through a green-textured glass, repeating its image in multiple positions. The glass's refractions would cause their subtle deformations, engendered by minor variations of thickness and pigment concentration that compose the glass’s honeycomb-like texture, creating new optic and chromatic phenomena. A myriad of fables is always possible when looking at Hattnher's paintings, with an encouraging will to imagine about the painter's visual experiences.

Proposing an aesthetics of receptivity, Hattnher’s deliberations always respond to demands presented by the painting in an open dialogue with the pictorial and poetic situations he is facing. These meditative resonances are crucially singular to the moment they are timely anchored, which cannot be repeated and are, therefore, intensely unique. In Timing notes, the artist presents serenely transcendent paintings with well-defined, balanced lyrical magnitude, structuring a mirrored flux that goes back and forth between memorial experiences and visual incidents. Hattnher, a musician with the keenest ears and eyes to the surrounding euphonic soundscape, actively listens to the painting, waiting for a cue to start playing. Always uncertain, this cue is sometimes unheard but sensed; at other times, extremely loud but missed. This seismic indication can be misleading—what often makes him cover and repaint the canvas—but also frequently precise, composing a changeable mosaic of chords. An image, then, is a matter of time.

Note

[1] As in Liz Cora, Words to be looked at: Language in 1960s art. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2010, p. 50.

/

Notas de tempo

O ato de tomar notas é central no comportamento do observador perspicaz: escrever ou desenhar brevemente logo após se deparar com algo bonito, embora a maioria das coisas dignas de nota sejam inefáveis. Um labor que almeja preservar uma memória aberta, a nota – em seu jogo polissêmico, de uma indicação musical a um pensamento anotado – tem a liberdade de não abranger narrativas completas, não oferecendo nenhum contexto rigoroso, mas anotações atraentes para a co-criação fabulativa. Ao mesmo tempo, a nota propõe um sentido empático de compartilhar impressões pessoais do mundo exterior de modo generoso e honesto, reafirmando a subjetividade de quem a tomou enquanto convida o observador a experimentar um ponto de vista ou um estado mental. Em Notas de tempo (Timing notes), Thiago Hattnher (1990, São Paulo, Brasil) apresenta, de forma empática, uma constelação autobiográfica de notas pictóricas que carregam uma sensação de atemporalidade, viva na carnalidade de memórias já passadas e na potência evocativa de saudades duradouras.

A dinâmica pendular entre intenção esperançosa e espontânea decadência – bem como a pintura e a música lidam similarmente com o tempo – pode sintetizar a habilidade de Hattnher de travar elementos esquivos e ambíguos em concisas pinturas de pequeno formato. Congregando delicadas escolhas cromáticas e formais e uma extrema atenção ao suporte – que varia de juta grossa, madeira coletada, fino linho e tela de algodão –, seus trabalhos são recordações de imagens e experiências insubmissos a um gênero disciplinar estrito. A qualidade prateada de pétalas banhadas pela lua coexiste com paisagens lembradas, enevoadas como miragens, em matizados campos geométricos. Mesmo através de um severo processo de acumulação, o artista pinta apenas o suficiente para deixar espaço para o intocado.

Como diagramas não-lineares, as pinturas de Hattnher são usualmente compostas por corpos de cor, arranjos florais e paisagens concebidas em uma estrutura geométrica aparentemente intuitiva. Elementos contrastantes, sutis embora súbitos, agem como rompantes compositivos e cromáticos sempre direcionados a um intento rítmico, cheio de vibrações e tons heterogêneos, de canções-de-ninar a dramáticas sonatas. Postos na mesma hierarquia – um retângulo azul não se comporta como fundo, assim como um buquê de flores ou a silhueta de um monte não obedecem à superioridade histórica atribuída à figura –, esses elementos são todos experimentos imagéticos e poéticos interessados na discussão de ritmo, intervalo e duração. Como uma partitura, eles são intrincados em múltiplas camadas, dissertando sobre esses assuntos não apenas na relação entre si, mas individualmente: cada parte é um microcosmo que reflete decisões densas acerca da fatura, da iluminação pela construção de camadas, do hiato entre as demãos de tinta e do ameaçador momento de parar e considerar a pintura finalizada. Quando compostos, seus elementos congregam a harmonia entre as cordas, os metais, as madeiras, as percussões e as teclas de uma orquestra, cada uma desempenhando um papel específico individualmente e em conjunto.

Hattnher, ademais, reitera a ambivalência de lidar com a imagem enquanto ela está sendo feita. O desafio e o baile, a pausa e a ação, o destino indomável e o planejado desejo – “Eu não ouço a música quando a escrevo. Eu a escrevo para poder ouvir algo que ainda não ouvi”, como posto por John Cage [1], fulcral na prática de Hattnher. Essa postura aberta não apenas ilustra as dinâmicas fluidas do processo criativo, mas coloca o pintor, uma figura de ação, no âmbito da quietude, enquanto a imagem, usualmente vista como passiva, assume o protagonismo. A pintura performa, mesmo imóvel.

Como na música In a Landscape, de 1948, de John Cage e Stephen Dudry, os dois artistas envergam um robusto repertório de música erudita para a experimentação. A música, multissensorial e melancólica, não referencia uma tradição musical ocidental em citações de fácil reconhecibilidade, mas em profunda compreensão e subversão de sua estrutura. Experimentações análogas são familiares a Hattnher, e o pareamento entre música e pintura na leitura de seu trabalho – e também na supracitada In a Landscape – não se faz por acaso. Os aspectos vívidos do processo criativo através da reoperação de conhecimento erudito podem ser exemplificados pela profunda admiração de Hattnher pelas obras de Albert York e Giorgio Morandi, para citar alguns – a justaposição da natureza-morta e da paisagem nas pinturas de York, principalmente nas produzidas entre 1982 e 1983; e a dissolução, por Morandi, de uma barragem histórica que tentaria evitar a mistura entre abstração e figuração.

Com pinceladas que complexificam timbres, as pinturas de Hattnher equilibram a modéstia de uma tentativa – como se proclamasse o descompromisso de ser apenas uma tentativa – e o deslumbramento de seu poder assertivo, sempre ancorado em observações da história da pintura. O artista transmuta essa ambiguidade em retângulos desnivelados, na heterogeneidade da fatura dos corpos cromáticos e no ativo diálogo com grandes temas da disciplina. Nessa exposição, há uma referência direta às últimas flores pintadas por Édouard Manet em uma publicação de 1988 dedicada a esse tópico. Ao pintar sua capa – o que Hattnher já fez com livros sobre Louise Bourgeois, Pablo Picasso, Cy Twombly e John Cage (este último de novo, como um refrão) –, ele não apenas referencia as próprias últimas flores de Manet, mas as reminiscências memoriais que cercam suas relações com essas pinturas, sejam elas através ou fora do livro mencionado: a atmosfera em marrom escuro das naturezas-mortas ao fundo de cada vaso de flor; a deliberação de certas pinceladas que, sozinhas, compõem pétalas; as molduras em linho e madeira dourada que coroam a maioria dessas pinturas mas que foram deixadas de lado nas reproduções do livro; a luva verde-esmeralda ligeiramente desbotada pelo sol; o aspecto granulado da pintura escolhida para estampar a capa, fotografada analogicamente.

Em outro trabalho, Hattnher pinta um mosaico turquesa de lírios brancos sobre uma vasta e árida paisagem cisada por uma estrada sinuosa. Sugere a imagem de um só lírio, replicado como se visto através de um vidro verde escamado, repetindo sua imagem em múltiplas posições. As refrações do vidro causariam suas sutis deformações, engendradas pelas mínimas variações de espessura e concentração de pigmento que compõem a textura do vidro, criando novos e cambiantes fenômenos ópticos e cromáticos. Uma miríade de fabulações é sempre possível ao observar as pinturas de Hattnher, com um ímpeto que encoraja a imaginação sobre as experiências visuais do pintor durante a produção das obras.

Propondo uma estética da receptividade, as deliberações de Hattnher sempre respondem a demandas apresentadas pela pintura em um aberto diálogo com as situações poéticas e pictóricas que ele encara naqueles específicos momentos. Esses ecos meditativos são particulares ao momento em que estão ancorados, reiterando sua irrepetibilidade. Em Notas de tempo (Timing notes), o artista apresenta pinturas serenas com equilibradas magnitudes líricas, a estruturar um fluxo espelhado que oscila entre experiências memoriais e incidentes visuais. Hattnher, um musicista com atentíssimos olhos e ouvidos às eufônicas paisagens sonoras que o cercam, ativamente escuta a pintura, esperando por uma deixa a para começar a tocar. Sempre incerto, esse sinal é, em muitos casos, não ouvido, mas sentido; em outros, ensurdecedor, mas fugaz. Essa indicação sísmica pode conduzir ao erro – o que faz com que o pintor cubra e repinte a tela com frequência – mas ser notadamente precisa, compondo um mosaico mutável de acordes. Uma imagem, então, é uma questão de tempo.

Nota

[1] Cf. Liz Cora, Words to be looked at: Language in 1960s art. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2010, p. 50.

Texto originalmente publicado na exposição “Timing notes”, curada por Brandy Carstens, na galeria Jeremy Scholar, em Londres, de 1 de julho a 30 de agosto de 2024.

Jeremy Scholar, Londres

Note-taking is central to the keen observer’s behavior: briefly writing or drawing after perceiving something beautiful, despite most noteworthy things being ineffable. A labor of attempting to preserve an open memory, the note—in its polysemic play, from a musical indication to an annotated thought—holds a freedom of not comprising complete narratives, offering no rigorous context but rather alluring annotations for tale co-creation. At the same time, it proposes an empathetic sense of sharing personal impressions of the outer world generously and honestly, reaffirming one’s subjectivity while inviting the observer to experience a point of view and a state of mind. In Timing notes, Thiago Hattnher (b. 1990, São Paulo, Brazil) empathetically presents an autobiographical constellation of pictorial notes that carry a sense of timelessness, alive in the fleshiness of outdated memories and the evocative potency of lasting longings.

This pendulum dynamic between hopeful intent and candid decay—but also between how painting and music similarly deal with time—can synthesize Hattnher's ability to lock fleeting and ambiguous elements into concise, small-scale paintings. Congregating delicate chromatic and formal choices and extreme attention to the medium—which varies from rough burlap, collected wood, fine linen, and cotton canvases—, his works are recollections of images and experiences unrestricted by a rigid disciplinary genre. The moonlit, silvery quality of petals coexist with mirage-like landscapes, fogged, remembered, in hued geometric fields. Even through a severe accumulation process, the artist paints just enough to leave room for the untouched.

As non-linear diagrams, Hattnher’s paintings usually comprise color blocks, flower arrangements, and landscapes devised into a seemingly intuitive geometrical structure. Slight but sudden contrasting elements act as compositive and chromatic outbursts always directed towards a rhythmic intention, full of heterogeneous vibrations and tones, from lullabies to dramatic sonatas. Put in the same hierarchy—a blue rectangle is not a background, just as a flower bouquet or the silhouette of a hill do not obey the historical superiority attributed to a figure—, they are all imagetic and poetic experiments on rhythm, interval, and duration. Akin to a concert chart, these elements are multilayered, discoursing on these subjects not only in the relations between each other but within themselves: each part is a microcosm that reflects dense choices of paint handling, illumination by layer construction, hiatus between paint coats, and the ominous moment to stop and consider it finished. When assembled, they are finely orchestrated like the woodwinds, brass, percussion, strings, and keyboards of a symphony, each fulfilling a specific role individually and as a whole.

Hattnher reiterates the ambivalence of dealing with the image while it is being made. The defiance and the ball, the pause and the action, the uncontrolled fate and the planned desire—“I don’t hear music when I write it. I write it in order to hear something I haven’t heard yet”, as stated by John Cage [1], deeply impactful in Hattnher’s practice. This open posture not only illustrates the nuanced dynamics of the creative process but places the painter, a figure of action, into a realm of stillness, while the image, usually seen as passive, takes center stage. The painting performs, even unmoving.

As in John Cage’s and Stephen Drury’s In a Landscape, music from 1948, the two artists bend a robust repertoire of erudite music into experimentation. The multisensorial and melancholy music do not reference a Western musical tradition in easily recognizable citations but in a deep comprehension—and subversion—of its structure. These experimentations are familiar to Hattnher, and the pairing of music and painting in the reading of his work—and also in Cage’s and Drury’s In a Landscape—is not by chance. The vivid aspects of the creative process analogous to the reoperation of erudite knowledge can be exemplified through Hattnher’s profound admiration of the works of Albert York and Giorgio Morandi, to name just a few—the juxtaposition of still life and landscape in York’s paintings, mainly the ones between 1982 and 1983; and dissolution of the dem that often prevents the merging of abstraction and figuration in Morandi’s work.

In timbre-enriching brushstrokes, Hattnher’s paintings balance the modesty of an attempt—as if proclaiming it is just a seemingly effortless attempt—and the dazzle of its assertive power, always rooted in profound erudition. The artist transmutes this ambiguity in the uneven rectangles, in the heterogeneity of the paint handling in the chromatic bodies, and in the active dialogue with grand themes of the history of painting—an exchange solidified through Hattnher’s awareness of the tradition of his craft. In this show, there is a direct reference to the last flowers painted by Édouard Manet through a 1988 dedicated book. By painting its cover—what Hattnher has previously done with publications on Louise Bourgeois, Pablo Picasso, Cy Twombly, and John Cage (again, as a chorus)—, he does not only refer to Manet’s painted flowers themselves but the endless reminiscences of memory that surround his relations with these paintings through and outside the book: the dark brown still-life atmosphere that was in the back of each flower vase; the decisiveness of some single brushstrokes that compose petals; the linen-and-gilded-wood frames that crowned most of the flower paintings but were left out in the book’s reproductions; the slightly faded, sunburnt book sleeve in emerald green; the analogic grainy aspect of the photographed painting elected to stamp its cover.

In another work, Hattnher paints a turquoise mosaic of white lilies under a vast, arid landscape scarred by a curved path. It resembles the image of the same lily but replicated as if seen through a green-textured glass, repeating its image in multiple positions. The glass's refractions would cause their subtle deformations, engendered by minor variations of thickness and pigment concentration that compose the glass’s honeycomb-like texture, creating new optic and chromatic phenomena. A myriad of fables is always possible when looking at Hattnher's paintings, with an encouraging will to imagine about the painter's visual experiences.

Proposing an aesthetics of receptivity, Hattnher’s deliberations always respond to demands presented by the painting in an open dialogue with the pictorial and poetic situations he is facing. These meditative resonances are crucially singular to the moment they are timely anchored, which cannot be repeated and are, therefore, intensely unique. In Timing notes, the artist presents serenely transcendent paintings with well-defined, balanced lyrical magnitude, structuring a mirrored flux that goes back and forth between memorial experiences and visual incidents. Hattnher, a musician with the keenest ears and eyes to the surrounding euphonic soundscape, actively listens to the painting, waiting for a cue to start playing. Always uncertain, this cue is sometimes unheard but sensed; at other times, extremely loud but missed. This seismic indication can be misleading—what often makes him cover and repaint the canvas—but also frequently precise, composing a changeable mosaic of chords. An image, then, is a matter of time.

Note

[1] As in Liz Cora, Words to be looked at: Language in 1960s art. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2010, p. 50.

/

Notas de tempo

O ato de tomar notas é central no comportamento do observador perspicaz: escrever ou desenhar brevemente logo após se deparar com algo bonito, embora a maioria das coisas dignas de nota sejam inefáveis. Um labor que almeja preservar uma memória aberta, a nota – em seu jogo polissêmico, de uma indicação musical a um pensamento anotado – tem a liberdade de não abranger narrativas completas, não oferecendo nenhum contexto rigoroso, mas anotações atraentes para a co-criação fabulativa. Ao mesmo tempo, a nota propõe um sentido empático de compartilhar impressões pessoais do mundo exterior de modo generoso e honesto, reafirmando a subjetividade de quem a tomou enquanto convida o observador a experimentar um ponto de vista ou um estado mental. Em Notas de tempo (Timing notes), Thiago Hattnher (1990, São Paulo, Brasil) apresenta, de forma empática, uma constelação autobiográfica de notas pictóricas que carregam uma sensação de atemporalidade, viva na carnalidade de memórias já passadas e na potência evocativa de saudades duradouras.

A dinâmica pendular entre intenção esperançosa e espontânea decadência – bem como a pintura e a música lidam similarmente com o tempo – pode sintetizar a habilidade de Hattnher de travar elementos esquivos e ambíguos em concisas pinturas de pequeno formato. Congregando delicadas escolhas cromáticas e formais e uma extrema atenção ao suporte – que varia de juta grossa, madeira coletada, fino linho e tela de algodão –, seus trabalhos são recordações de imagens e experiências insubmissos a um gênero disciplinar estrito. A qualidade prateada de pétalas banhadas pela lua coexiste com paisagens lembradas, enevoadas como miragens, em matizados campos geométricos. Mesmo através de um severo processo de acumulação, o artista pinta apenas o suficiente para deixar espaço para o intocado.

Como diagramas não-lineares, as pinturas de Hattnher são usualmente compostas por corpos de cor, arranjos florais e paisagens concebidas em uma estrutura geométrica aparentemente intuitiva. Elementos contrastantes, sutis embora súbitos, agem como rompantes compositivos e cromáticos sempre direcionados a um intento rítmico, cheio de vibrações e tons heterogêneos, de canções-de-ninar a dramáticas sonatas. Postos na mesma hierarquia – um retângulo azul não se comporta como fundo, assim como um buquê de flores ou a silhueta de um monte não obedecem à superioridade histórica atribuída à figura –, esses elementos são todos experimentos imagéticos e poéticos interessados na discussão de ritmo, intervalo e duração. Como uma partitura, eles são intrincados em múltiplas camadas, dissertando sobre esses assuntos não apenas na relação entre si, mas individualmente: cada parte é um microcosmo que reflete decisões densas acerca da fatura, da iluminação pela construção de camadas, do hiato entre as demãos de tinta e do ameaçador momento de parar e considerar a pintura finalizada. Quando compostos, seus elementos congregam a harmonia entre as cordas, os metais, as madeiras, as percussões e as teclas de uma orquestra, cada uma desempenhando um papel específico individualmente e em conjunto.

Hattnher, ademais, reitera a ambivalência de lidar com a imagem enquanto ela está sendo feita. O desafio e o baile, a pausa e a ação, o destino indomável e o planejado desejo – “Eu não ouço a música quando a escrevo. Eu a escrevo para poder ouvir algo que ainda não ouvi”, como posto por John Cage [1], fulcral na prática de Hattnher. Essa postura aberta não apenas ilustra as dinâmicas fluidas do processo criativo, mas coloca o pintor, uma figura de ação, no âmbito da quietude, enquanto a imagem, usualmente vista como passiva, assume o protagonismo. A pintura performa, mesmo imóvel.

Como na música In a Landscape, de 1948, de John Cage e Stephen Dudry, os dois artistas envergam um robusto repertório de música erudita para a experimentação. A música, multissensorial e melancólica, não referencia uma tradição musical ocidental em citações de fácil reconhecibilidade, mas em profunda compreensão e subversão de sua estrutura. Experimentações análogas são familiares a Hattnher, e o pareamento entre música e pintura na leitura de seu trabalho – e também na supracitada In a Landscape – não se faz por acaso. Os aspectos vívidos do processo criativo através da reoperação de conhecimento erudito podem ser exemplificados pela profunda admiração de Hattnher pelas obras de Albert York e Giorgio Morandi, para citar alguns – a justaposição da natureza-morta e da paisagem nas pinturas de York, principalmente nas produzidas entre 1982 e 1983; e a dissolução, por Morandi, de uma barragem histórica que tentaria evitar a mistura entre abstração e figuração.

Com pinceladas que complexificam timbres, as pinturas de Hattnher equilibram a modéstia de uma tentativa – como se proclamasse o descompromisso de ser apenas uma tentativa – e o deslumbramento de seu poder assertivo, sempre ancorado em observações da história da pintura. O artista transmuta essa ambiguidade em retângulos desnivelados, na heterogeneidade da fatura dos corpos cromáticos e no ativo diálogo com grandes temas da disciplina. Nessa exposição, há uma referência direta às últimas flores pintadas por Édouard Manet em uma publicação de 1988 dedicada a esse tópico. Ao pintar sua capa – o que Hattnher já fez com livros sobre Louise Bourgeois, Pablo Picasso, Cy Twombly e John Cage (este último de novo, como um refrão) –, ele não apenas referencia as próprias últimas flores de Manet, mas as reminiscências memoriais que cercam suas relações com essas pinturas, sejam elas através ou fora do livro mencionado: a atmosfera em marrom escuro das naturezas-mortas ao fundo de cada vaso de flor; a deliberação de certas pinceladas que, sozinhas, compõem pétalas; as molduras em linho e madeira dourada que coroam a maioria dessas pinturas mas que foram deixadas de lado nas reproduções do livro; a luva verde-esmeralda ligeiramente desbotada pelo sol; o aspecto granulado da pintura escolhida para estampar a capa, fotografada analogicamente.

Em outro trabalho, Hattnher pinta um mosaico turquesa de lírios brancos sobre uma vasta e árida paisagem cisada por uma estrada sinuosa. Sugere a imagem de um só lírio, replicado como se visto através de um vidro verde escamado, repetindo sua imagem em múltiplas posições. As refrações do vidro causariam suas sutis deformações, engendradas pelas mínimas variações de espessura e concentração de pigmento que compõem a textura do vidro, criando novos e cambiantes fenômenos ópticos e cromáticos. Uma miríade de fabulações é sempre possível ao observar as pinturas de Hattnher, com um ímpeto que encoraja a imaginação sobre as experiências visuais do pintor durante a produção das obras.

Propondo uma estética da receptividade, as deliberações de Hattnher sempre respondem a demandas apresentadas pela pintura em um aberto diálogo com as situações poéticas e pictóricas que ele encara naqueles específicos momentos. Esses ecos meditativos são particulares ao momento em que estão ancorados, reiterando sua irrepetibilidade. Em Notas de tempo (Timing notes), o artista apresenta pinturas serenas com equilibradas magnitudes líricas, a estruturar um fluxo espelhado que oscila entre experiências memoriais e incidentes visuais. Hattnher, um musicista com atentíssimos olhos e ouvidos às eufônicas paisagens sonoras que o cercam, ativamente escuta a pintura, esperando por uma deixa a para começar a tocar. Sempre incerto, esse sinal é, em muitos casos, não ouvido, mas sentido; em outros, ensurdecedor, mas fugaz. Essa indicação sísmica pode conduzir ao erro – o que faz com que o pintor cubra e repinte a tela com frequência – mas ser notadamente precisa, compondo um mosaico mutável de acordes. Uma imagem, então, é uma questão de tempo.

Nota

[1] Cf. Liz Cora, Words to be looked at: Language in 1960s art. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2010, p. 50.

Texto originalmente publicado na exposição “Timing notes”, curada por Brandy Carstens, na galeria Jeremy Scholar, em Londres, de 1 de julho a 30 de agosto de 2024.